Why California’s Trucking Failures Make Africa the Next Freight Frontier

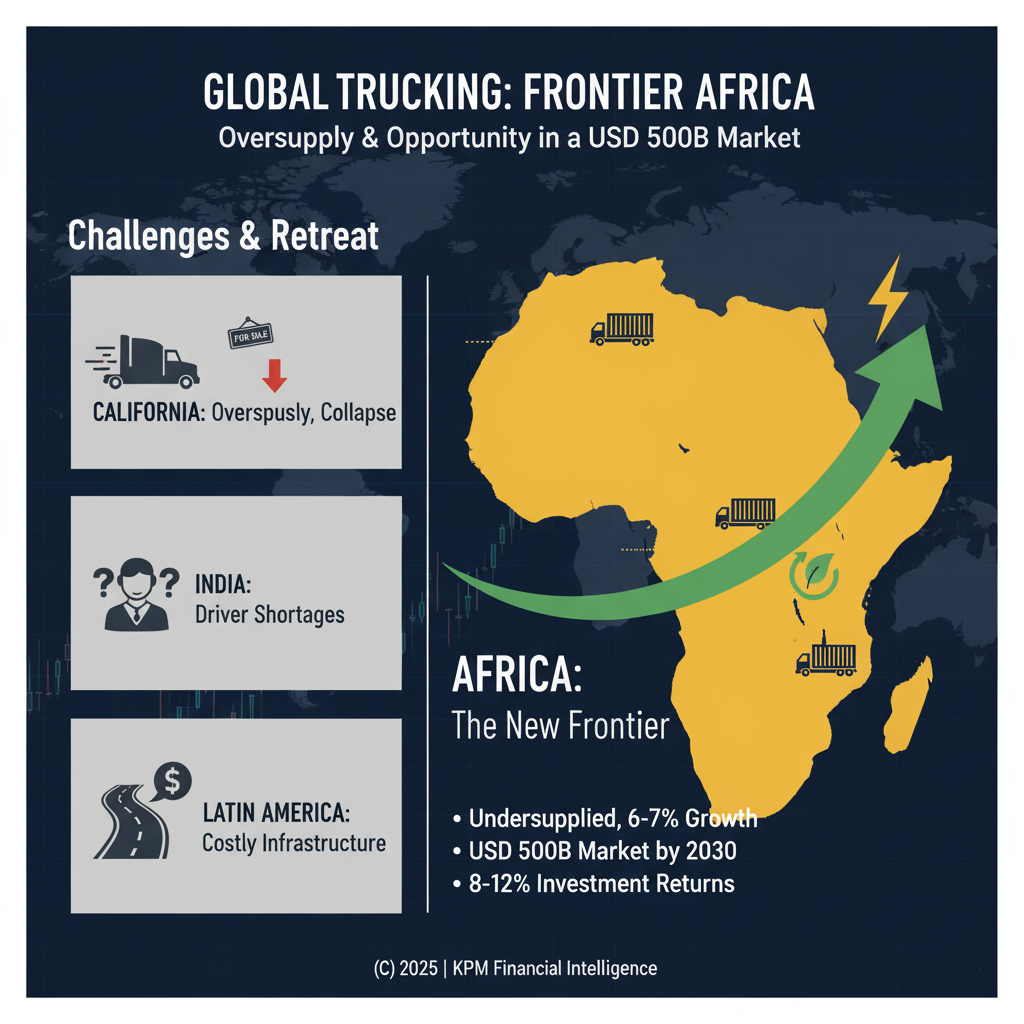

California’s trucking collapse shows oversupply and retreat. India faces driver shortages, Latin America struggles with costly roads, and Africa—undersupplied but growing 6–7% annually toward USD 500B—emerges as the frontier, offering 8–12% IRRs where others strain.

Why California’s Trucking Failures Make Africa the Next Freight Frontier

In California, some of the state’s most established trucking firms are shutting down. Imports at the Port of Los Angeles fell nearly 12% year-on-year in the first half of 2025, while the Cass Freight Index shows volumes down almost 8% compared with pre-2020 levels. Diesel prices hover near $4.30 a gallon, insurance premiums have risen nearly 9% annually, and compliance with emissions standards has become a balance-sheet strain. Publicly traded carriers such as Knight-Swift (NYSE:KNX), J.B. Hunt (NASDAQ:JBHT), and Old Dominion (NASDAQ:ODFL) have all issued margin warnings. The iShares U.S. Transportation ETF (BATS:IYT) is down more than 15% in twelve months. California today represents contraction: too many trucks, too few loads, and an oversaturated market in retreat.

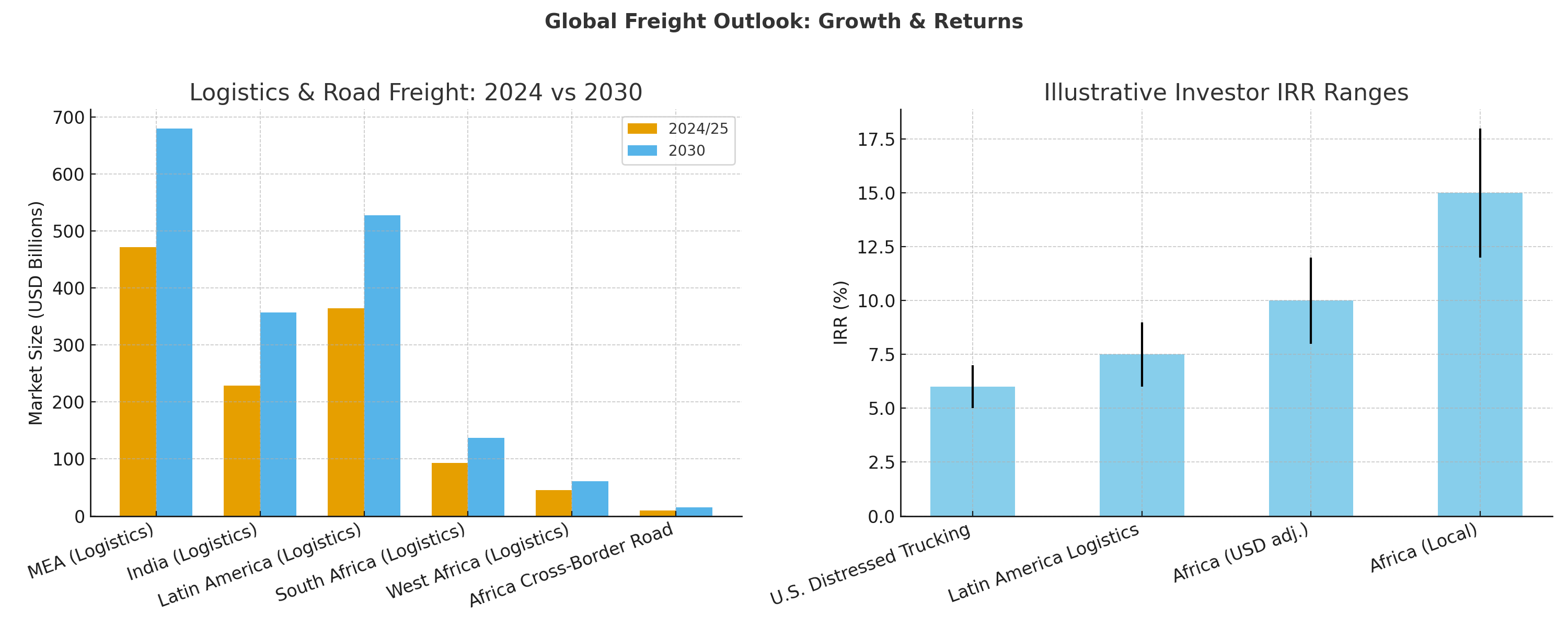

Africa tells a different story. Its freight and logistics market, valued at roughly USD 320 billion in 2025, is projected to surpass USD 500 billion by 2030, expanding at 6–7% annually—twice the global average. More than 80% of goods still move by road, but fleets are old—trucks average over 15 years in Nigeria and Kenya—and border delays add three to five days to journeys, driving logistics costs to 20–40% of product value compared with 8–10% in advanced economies. These inefficiencies weigh on performance, yet in a market where demand is climbing, they represent opportunity rather than decline.

Investors already have entry points through listed firms such as Imperial Logistics (JSE:IPL), Grindrod (JSE:GND), and Prosus (AMS:PRX), which reflect Africa’s expanding logistics footprint. Freight is always a macroeconomic signal: in the U.S., downturns in trucking volumes often precede recessions, and California’s collapse reflects weak imports, muted manufacturing, and supply chains shifting from China. Africa’s pressures instead come from growth—surging trade, urbanisation, and industrialisation outpacing infrastructure. Both regions show trucking as the economy’s thermometer, but while California signals contraction, Africa signals acceleration.

The first question investors ask is whether Africa’s forecasts are credible. Current estimates are grounded in AfDB and World Bank data. Four countries—South Africa, Nigeria, Egypt, and Kenya—account for roughly 60% of today’s USD 320 billion market. South Africa’s logistics industry alone, valued at USD 14.7 billion in 2025, is projected to approach USD 20 billion by 2030. East Africa’s trucking corridors—Mombasa to Nairobi, Kampala, Kigali—are expanding closer to 9–10% annually, fuelled by construction and consumer demand.

Nigeria’s Lagos–Abidjan corridor, one of West Africa’s busiest, is forecast to handle freight growth of 7% per year through 2030. These numbers are supported by hard demographic trends: Africa’s population will exceed 1.5 billion by 2030, urbanisation is accelerating at nearly 4% annually, and consumer spending is projected to rise from USD 1.4 trillion in 2020 to USD 2.1 trillion by 2030. In other words, demand-side growth is not speculative—it is structural.

Policy reform still lags. The African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) is only partially implemented—tariff schedules and customs harmonisation remain incomplete—so it should be seen as a long-term catalyst rather than an immediate driver. In the near term, regional blocs carry more weight: the EAC has cut border delays by up to 70% with electronic clearance, SADC is upgrading the Durban–Johannesburg corridor, and ECOWAS is pushing the Lagos–Abidjan highway.

Financing capacity is the next hurdle. With 80% of trucking firms running fewer than ten vehicles, fragmentation weakens balance sheets and SME default rates range from 12–18% annually. Yet blended finance is changing the risk profile. DFIs such as the IFC, AfDB, and Proparco are supplying guarantees and first-loss capital, bringing effective yields into the 8–12% USD range—well above developed market returns. For investors, that shifts trucking from a fragile SME play into a structured credit opportunity with stabilized returns.

Infrastructure remains the biggest bottleneck. The AfDB estimates Africa faces a USD 130 billion annual financing gap, with transport accounting for about 40%. Of this, USD 20–25 billion a year is realistically open to private capital through PPPs in toll roads, dry ports, and logistics parks. Precedents exist: Kenya’s Mombasa–Nairobi expressway has drawn in private equity and sovereign investors, while Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire are advancing PPP-driven upgrades along key corridors. Yet not all delays are physical—around 40% of logistics slowdowns stem from border inefficiencies. Digitized customs, harmonized inspection standards, and reduced discretionary checks often deliver faster returns than pouring asphalt.

Comparisons with other emerging markets highlight Africa’s trajectory. In India, trucking struggles with chronic driver shortages and rising compliance costs—driver attrition runs around 12% annually, and new Bharat Stage VI emissions standards have forced expensive fleet upgrades. Even so, logistics continues to grow 7–8% a year, driven by e-commerce, with consolidation plays such as Allcargo Logistics (NSE:ALLCARGO) shaping the market.

Latin America offers a different mirror. In Brazil, where 65% of goods move by road, poor infrastructure and fuel volatility echo Africa’s cost pressures. Logistics consumes 14–18% of GDP, well above the OECD’s 8–10% but still below Africa’s 20–40%. Operators like JSL Logística (BVMF:JSLG3) remain squeezed, while Mexico shows how integration into U.S. supply chains can change the story. Firms such as Grupo Traxión (BMV:TRAXIONA) are expanding rapidly through consolidation and digital platforms.

The Latin American experience shows how inefficiencies can be monetized. Investors have found exits through IPOs and M&A, including Rumo SA (BVMF:RAIL3) acquiring ALL (América Latina Logística). For Africa, the message is clear: today’s inefficiencies are tomorrow’s margins, and consolidation will follow once capital enters.

For global investors, returns are the hinge. Distressed U.S. trucking assets, such as fleets acquired from California bankruptcies, may yield 5–7% unlevered returns after restructuring. In Africa, logistics and infrastructure projects can generate 12–18% IRRs in local currency, or 8–12% in USD after FX hedging and sovereign risk premiums. The inefficiency premium is real: high logistics costs mean that even small gains—cutting border wait times by 10%, or reducing empty backhaul trips by 15%—translate into 3–5% margin improvements for operators. In a continent where logistics consumes up to 40% of product value, those gains are monetizable.

Capital structures are shifting quickly. Leasing, structured debt, and securitized trade finance are easing entry barriers, while IFC-backed leasing in Kenya and blended finance in Nigeria reduce SME risks. Green bonds tied to Euro VI and LNG trucks cut borrowing costs by up to 300 basis points, making Africa a transition play—diesel now, hybrids and LNG next, electrification later.

Exits are clearer too: MSC’s USD 6.4B purchase of Bolloré Africa Logistics showed global appetite, while Imperial Logistics (JSE:IPL) and Grindrod (JSE:GND), along with PE firms like Helios and DPI, highlight active deal flow. Sustainability strengthens the case as fleet renewal and hybrid depots deliver quick emission gains. For investors, this is less a green bet than a profitable transition. California shows oversupply collapse; Latin America monetises inefficiency through JSL Logística (BVMF:JSLG3) and Grupo Traxión (BMV:TRAXIONA); India grows steadily with Allcargo (NSE:ALLCARGO). Africa sits earlier on that curve—fragmented but expanding, inefficient yet investable. Inefficiency in California is collapse; in Africa it is frontier arbitrage.