When Politics Threatens Oil: The Economic Implications of Machar’s Charges

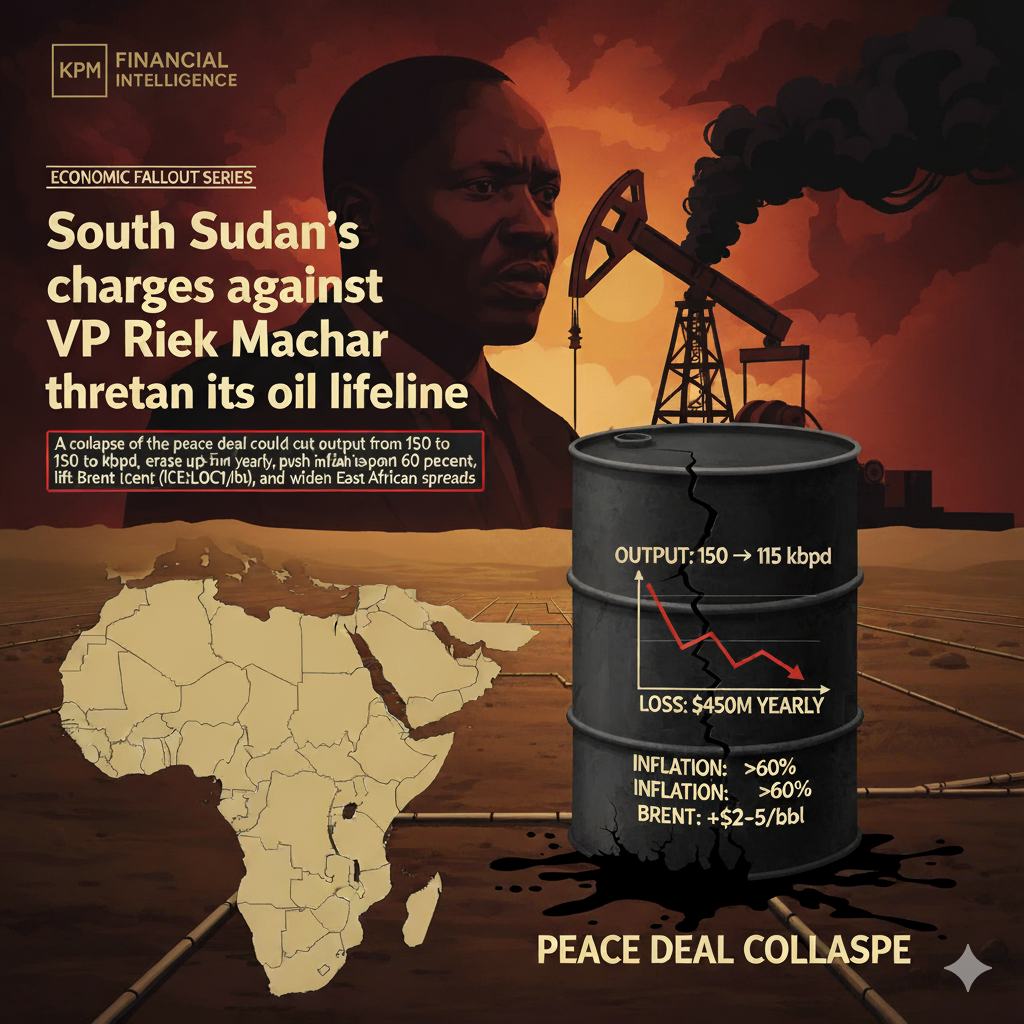

South Sudan’s charges against VP Riek Machar threaten its oil lifeline. A collapse of the peace deal could cut output from 150 to 115 kbpd (thousand barrels per day), erase up to $450m yearly, push inflation beyond 60 percent, lift Brent (ICE:LCOc1) by $2–5/bbl, and widen East African spreads.

South Sudan’s political rupture in September 2025 has shifted from domestic intrigue to a global market risk. First Vice President Riek Machar, co-guarantor of the fragile 2018 peace deal, has been charged with treason, murder, and crimes against humanity and suspended from office. He remains under house arrest. February’s cabinet reshuffles were disruptive but left Machar untouched, allowing investors to dismiss them as routine turbulence. September is different: the arrest undermines the very framework that keeps South Sudan’s oil flowing. For markets, this is no longer background noise but a supply and fiscal shock that must be repriced.

I assess a forty percent probability that production slips by fifteen to twenty percent (baseline), a thirty percent probability of a collapse below one hundred and twenty thousand barrels per day (worst case), and only a thirty percent probability that output stabilizes at current levels of one hundred and fifty thousand barrels per day (best case). A barrel, abbreviated bbl, is the standard oil measure equal to forty-two US gallons. kbpd means “thousand barrels per day.”

The math is straightforward. Every ten thousand barrels per day equates to 3.65 million barrels annually. At Brent crude of ninety dollars per barrel, once adjusted for quality discounts, transit fees, and financing haircuts, Juba nets fifteen to thirty dollars per barrel. That means each ten thousand barrels per day lost costs fifty-five to one hundred and ten million dollars in fiscal revenue annually. Even without volume losses, harsher financing terms can shave five to ten dollars per barrel off the government’s netback, erasing hundreds of millions from the budget.

Best Case (thirty percent probability)

Output holds at one hundred and fifty kbpd under heightened security. Financing terms worsen: a five-dollar per barrel pre-payment haircut costs Juba about two hundred and seventy-four million dollars annually even with steady volumes. Brent remains range-bound but trades with a one to two dollar per barrel frontier premium. Inflation stays elevated near thirty-five percent year on year.

Baseline (forty percent probability)

Clashes trim output to one hundred and thirty kbpd. At twenty-five dollars per barrel netback, Juba loses roughly one hundred and eighty-three million dollars per year, or ten to fifteen percent of its oil budget. Across the netback range, the annual loss spans one hundred and ten to two hundred and nineteen million dollars. If financing discounts widen by ten dollars per barrel, another seventy-three million is lost. Inflation breaches forty-five percent within nine months. Brent carries a two to three dollar per barrel risk premium, widening front-end backwardation.

Worst Case (thirty percent probability)

The peace deal collapses and production falls to one hundred and fifteen kbpd. At mid netback, losses reach about three hundred and nineteen million dollars per year, with a possible range of one hundred and ninety-two to three hundred and eighty-three million. Add harsher financing, and the fiscal hole easily surpasses four hundred and fifty million — equal to more than a third of Juba’s annual budget. Reserves are drained, deficits monetized, and hyperinflation above sixty percent year on year becomes entrenched. Brent prices factor in a four to five dollar per barrel disruption premium.

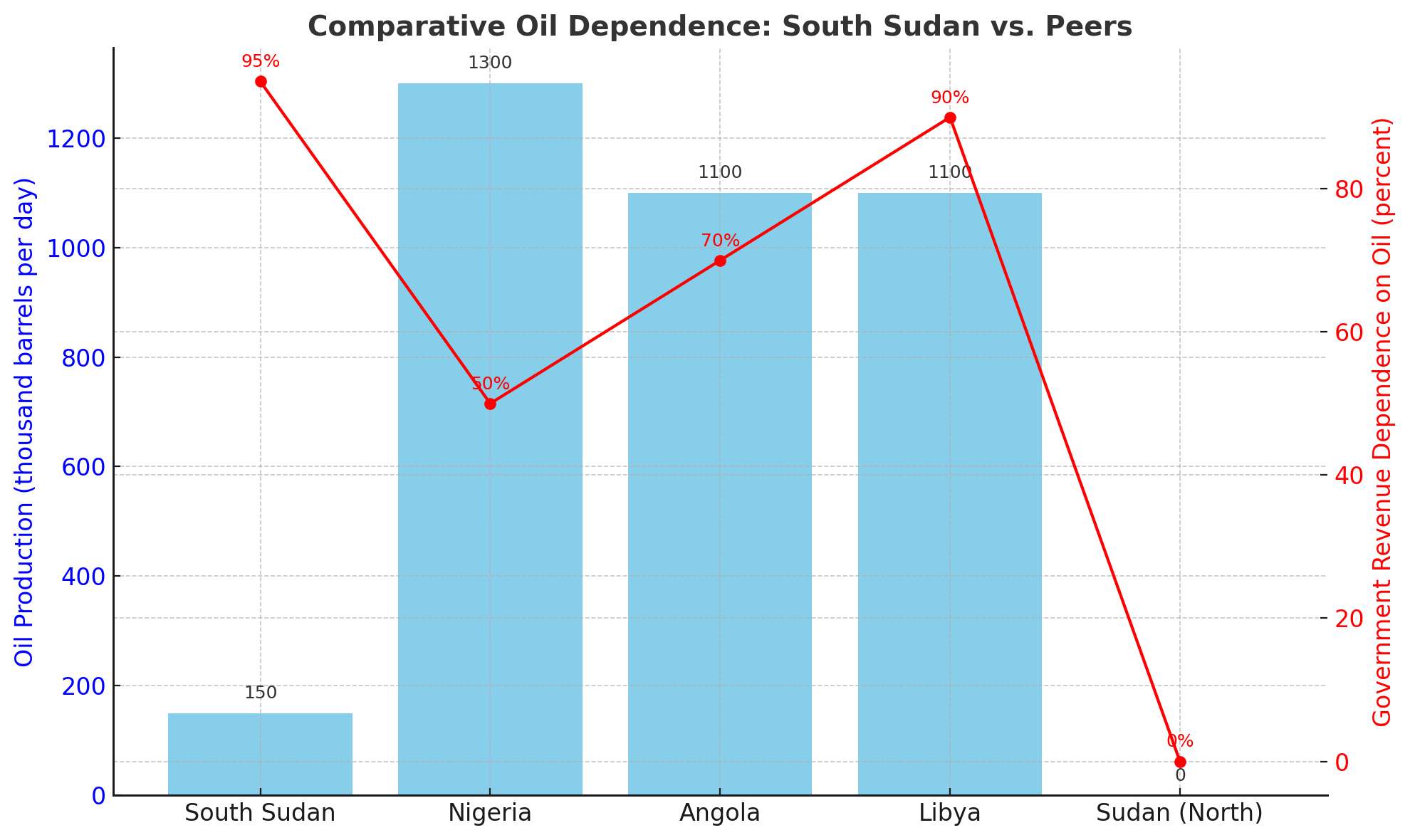

Comparative context matters. A twenty kbpd disruption is small in absolute terms, but like pipeline sabotage in Nigeria or field outages in Libya, these are marginal barrels that drive volatility. Traders build such risks into Brent spreads, and frontier barrels carry a disproportionate risk premium. South Sudan’s ninety-five percent oil dependence far exceeds Angola’s seventy percent or Nigeria’s fifty percent, magnifying the fiscal and FX consequences.

The chart below compares production scale with revenue dependence across key African producers.

Currency stress will be immediate. Every one hundred to two hundred million dollars of lost revenue widens the US dollar premium in South Sudan’s parallel market and lifts consumer inflation by five to ten percentage points within six to nine months. Given that more than eighty percent of food is imported, this shock translates directly into household hardship. The South Sudanese Pound weakens against the US Dollar Index (DXY), while regional spillovers affect Kenya’s Eurobonds (XS2115121659), Uganda’s fiscal balances, and frontier ETFs such as iShares MSCI Frontier (NYSE: FM).

Investor confidence in new exploration will vanish. Asian national oil companies and Gulf partners, previously courted for blocks, will not commit while political trust unravels. Mature fields will decline and South Sudan’s proven reserves of 3.5 billion barrels risk becoming stranded assets. Financing will increasingly depend on distressed pre-payment contracts with traders like Glencore (LSE: GLEN), further reducing the effective value per exported barrel.

The donor calculus compounds the risk. The United States, United Kingdom, and European Union have signaled that Machar’s prosecution undermines the peace deal. If development aid is frozen and replaced only by humanitarian relief, Juba loses its last external budget anchor. For lenders, this raises sovereign default probabilities and undermines concessional lending frameworks. In debt markets, this feeds into wider spreads across East Africa, as frontier investors reprice the region’s risk premium.

My judgment is clear. February’s reshuffles were noise; September’s charges are a structural break. Oil traders should price a higher Brent disruption premium of two to five dollars per barrel. Portfolio managers should widen risk premiums on frontier barrels by at least two hundred basis points and treat East African Eurobonds as more correlated with oil shocks than previously priced. Donors and financial institutions should prepare for arrears, defaults, and a pivot back to conflict economics.

History shows what happens when Kiir and Machar part ways: production collapses, revenues shrink, and hyperinflation follows. Unless compromise is restored, South Sudan’s oil future will be dictated not by reserves underground but by politics above it. For global markets, this translates into heightened attention to Brent (ICE: LCOc1), the US Dollar Index (DXY), Glencore (LSE: GLEN), and frontier sovereign spreads.