Ramani’s Digital Gamble Faces a Global Stress Test

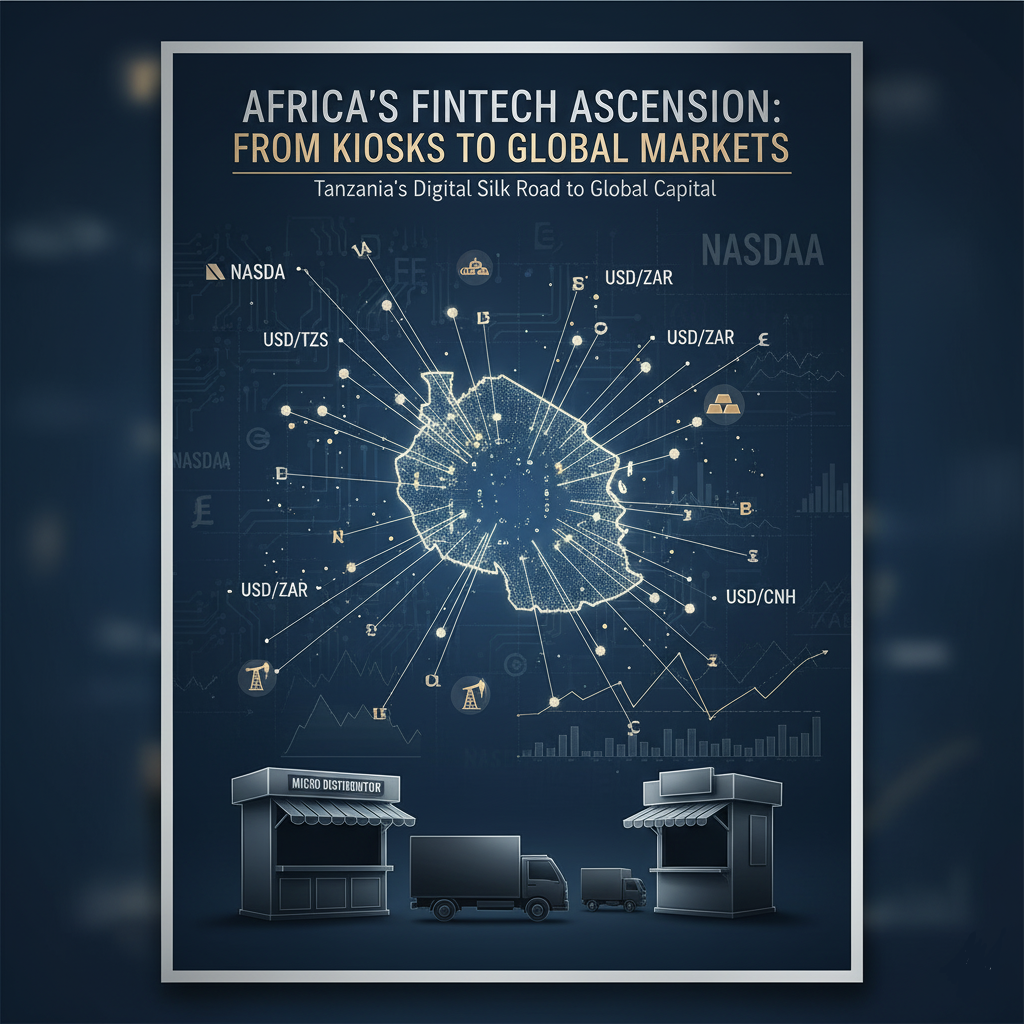

Tanzania’s fintech darling has disbursed $210m in loans to micro-distributors, but weak labor absorption, fragile demand, and rising global rates could expose it as more lender than SaaS — with ripple effects from Dar es Salaam to Wall Street.

Ramani has become one of the most talked-about startups in Tanzania’s tech ecosystem, promising to digitize and finance the micro-distributors who power the country’s consumer goods supply chain. Its model, part software platform and part lender, has been celebrated as an engine of financial inclusion, unlocking more than US$210 million in loans and reshaping how fast-moving consumer goods reach shelves. Yet behind the optimism lie structural risks that raise questions about whether this digital gamble can endure.

At the heart of Ramani’s proposition is a hybrid flywheel: distributors use its platform to track sales and inventory, Ramani leverages that data to extend short-cycle working-capital loans, and repayment performance feeds a cycle of further credit. On paper it is elegant, but in practice the company is far closer to a credit institution than a SaaS business, and that exposes it to risks that cumulative disbursement totals conveniently obscure. What matters is not the volume of capital pushed through the system but how resilient that loan book remains when consumer demand softens, inflation erodes household purchasing power, or the Tanzanian shilling (USD/TZS) depreciates against the dollar. In frontier credit models, non-performing loan ratios above 8 to 10 percent can destabilize balance sheets quickly, and without transparency on default rates, loan maturities, or cost of funds, it is impossible to judge whether Ramani is earning sustainable margins. If DFIs and venture lenders supply liquidity at 8 to 12 percent and distributors borrow at 18 to 22 percent, spread exists, but the margin can evaporate rapidly if repayment discipline weakens.

The geography of its operations adds another layer of fragility. The model works well in Dar es Salaam, where density, logistics infrastructure, and transaction volumes provide fertile ground. In smaller towns and rural areas the economics change: connectivity is patchy, distributor ticket sizes are far smaller, and data quality is inconsistent. Scaling horizontally across Tanzania, and later into markets such as Kenya, Uganda, or Zambia, is less a question of capital than of operational control, behavioral adoption, and repayment discipline. Convincing informal distributors to keep consistent digital records is a cultural hurdle as much as a technological one. If those inputs are weak, the credit algorithms misprice risk, and what appears to be smart underwriting becomes a hidden liability.

Even where adoption is strong, defensibility is thin. Ramani’s inventory dashboards, procurement systems, and sales tools are useful but hardly unique. Large FMCG multinationals like Coca-Cola (KO), Unilever (UL), and Diageo (DGE.L) could build proprietary distributor platforms overnight, and banks or mobile money operators already sit on transaction datasets that could be repurposed for lending. If better-capitalized incumbents decide to move down-market, Ramani’s supposed moat of data-driven financing could narrow to nothing. The very fact that its strongest asset is a loan book rather than intellectual property makes it more vulnerable to both competition and macroeconomic shocks.

Those shocks are not hypothetical. Inflation cycles in Tanzania have already squeezed household consumption, weakening distributor sales and, by extension, repayment capacity. A weaker shilling raises the cost of imported goods, compounding pressure on margins. Rising oil prices (CL=F) feed into higher transport costs, while falling copper (HG=F) or platinum (PL=F) prices reduce export revenues and put pressure on African currencies like the rand (USD/ZAR) or kwacha (USD/ZMW). Global liquidity flows reinforce the exposure: when U.S. 10-year Treasury yields (US10Y) rise, capital for frontier fintechs becomes scarcer and more expensive, raising Ramani’s cost of funds. When the Federal Reserve tightens, the knock-on effect reaches all the way to a kiosk in Dar es Salaam.

The risks Ramani faces are not idiosyncratic but echo those of its peers. Wasoko in Kenya and TradeDepot in Nigeria raised more than US$100 million each to digitize informal retail, only to find themselves squeezed by thin margins and rising defaults. Sokowatch and Twiga Foods in East Africa have also struggled with profitability beyond urban centers. In Asia, India’s Udaan and Indonesia’s Kudo dazzled investors with rapid growth but were forced to retrench when defaults mounted. Globally, the collapse of Greensill and the troubles at Klarna remind markets how fragile credit-first fintech models can be. Ramani’s trajectory so far fits into a broader pattern: fintechs that mistake loan growth for profitability and confuse gross disbursements with sustainable returns.

What comes next can be sketched across three scenarios. In the best case, default rates stay contained below five percent, DFIs continue to provide low-cost liquidity, and Ramani scales profitably into regional markets, perhaps even securitizing its loan book in capital markets. In the base case, urban penetration saturates, expansion into rural zones proves loss-making, and margins tighten, leaving the company dependent on new investment rather than internal cash generation. In the worst case, macro shocks push defaults into double digits, regulators tighten digital credit rules, and global capital dries up, forcing retrenchment and turning Ramani into a cautionary tale.

The implications stretch beyond Tanzania. Global investors increasingly view firms like Ramani as test cases for the invest-ability of African fintech. If it succeeds, Ramani could anchor a new sub-asset class of SME financing backed by real-time data, helping narrow spreads on African euro-bonds such as Nigeria’s 2031 issuance (NG2031=) or Kenya’s 2032 paper (KE2032=). That, in turn, could encourage portfolio inflows, strengthen currencies, and lower sovereign borrowing costs. If it stumbles, the opposite holds: spreads widen, investor appetite wanes, and the perception of fragility in African credit deepens. The fate of a Tanzanian startup can thus ripple into how global capital markets price African sovereign and corporate risk.

None of this diminishes the importance of what Ramani is trying to achieve. Tanzania’s distributors do face chronic inefficiencies, from lack of working capital to poor data visibility, and Ramani’s digital tools and credit lines offer solutions that can empower small businesses and reduce waste. The social and economic value is real. But potential is not inevitability. Without resilience — the ability to manage defaults when economies slow, to scale beyond urban hubs without burning cash, and to defend its model against competitors with deeper pockets — the digital caravan risks stalling. Ramani’s gamble is not just a Tanzanian story. It is a test case of how global capital markets will value, and judge, the next generation of African fintech.