Nigeria’s Inflation Trap Is Strangling Trade

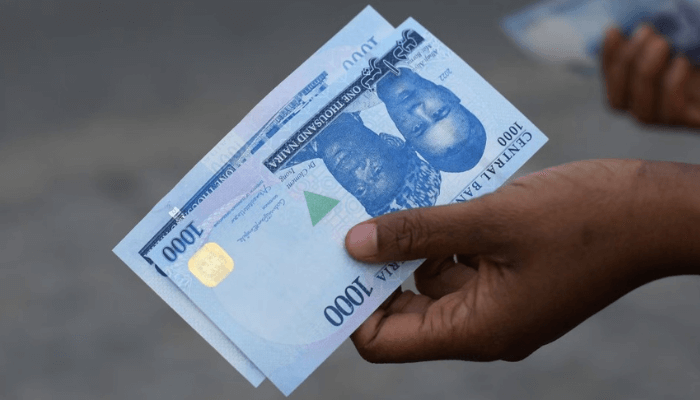

Nigeria’s trade growth slid from 2.04 % to 1.29 % as inflation above 20 % and a 26.75 % policy rate choke liquidity. The naira’s instability and high logistics costs expose a deeper disease—structural inefficiency that no tightening can cure.

Nigeria’s latest trade data reveal a structural weakening at the core of its economy. Growth in the trade sector has slowed across three consecutive quarters—from 2.04 percent in late 2024 to 1.78 percent in early 2025, and further down to 1.29 percent in the second quarter of this year. With trade contributing nearly one-fifth of national GDP, this sustained deceleration signals an economy losing its internal momentum as consumer demand, purchasing power, and business liquidity all erode simultaneously.

Inflation remains the most visible trigger, yet it operates within a web of deeper distortions. The Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) has pursued aggressive tightening to contain prices, pushing the benchmark interest rate to 26.75 percent. The policy has made short-term financing nearly unreachable for traders and distributors, whose operations depend heavily on revolving credit. At the same time, the naira’s volatility and rising logistics costs have amplified uncertainty, discouraging investment and freezing working capital across supply chains.

In Lagos, Onitsha, and Kano—the commercial lungs of Nigeria—traders report that sales turnover has fallen by as much as half despite full inventories. Power tariffs, transport fares, and port demurrage charges have squeezed profit margins beyond repair. Imported goods priced in U.S. dollars are increasingly treated as speculative stores of value rather than fast-moving merchandise, as merchants hedge against exchange-rate losses. The result is a contraction in retail liquidity: the informal networks that once absorbed inflationary shocks now transmit them directly into higher consumer prices.

Policy coordination is where the failure lies. Monetary restraint alone cannot suppress cost-push inflation that originates in infrastructure bottlenecks, energy pricing, and import dependency. Every rate hike deepens the liquidity squeeze while leaving logistics and structural inefficiencies intact. Nigeria’s fiscal authorities have yet to match monetary discipline with complementary reform—such as targeted trade finance, energy tariff rationalisation, or port modernisation. Without those measures, inflationary pressures simply shift from credit markets into the real economy.

The fiscal implications are already visible. As trade volumes contract, VAT and customs revenues are falling, narrowing fiscal space for public investment. Reduced infrastructure spending feeds directly into higher logistics costs, creating a circular trap: weak trade undermines revenue, poor infrastructure raises inflation, and inflation further weakens trade. Unless the state breaks this loop, Nigeria risks sliding into a pattern of stagnation masked by nominal growth.

Comparative experience across Africa underscores the urgency. Kenya and Ghana have also faced double-digit inflation, yet clearer coordination between monetary and fiscal policy has limited demand destruction. South Africa’s consumer-price inflation near six percent shows what happens when credibility anchors expectations and cost transmission channels are managed. Nigeria’s inflation, by contrast, remains entrenched because every cost shock—from FX depreciation to fuel levies—cascades through an economy still dependent on imports and inefficient logistics.

For investors, the signal is unmistakable. The trade sector that once offset inflation through higher sales volumes is now amplifying it. Listed consumer-goods firms such as Nestlé Nigeria [NGX:NESTLE], Dangote Sugar [NGX:DANGSUGAR], and Unilever Nigeria [NGX:UNILEVER] may report nominal revenue growth, but their real margins are deteriorating as household budgets shrink. The stock market’s optimism over foreign-exchange liberalisation conceals a more fundamental weakness: domestic consumption, the foundation of Nigeria’s private-sector growth model, is in retreat.

Nigeria’s challenge is not the absence of capacity but the absence of coherence. Inflation control through interest rates has sterilised liquidity while leaving the structural cost base untouched. A credible recovery demands synchronised reform: transparent FX auctions to stabilise the naira, accelerated port upgrades to reduce shipping delays, lower energy tariffs for SMEs, and accessible credit channels for distributors. Monetary restraint must operate alongside logistical reform, not in isolation.

Each quarter of slowing trade growth represents more than a statistical blip—it is proof of a shrinking domestic marketplace. Inflation is the symptom, but inefficiency is the disease. Unless Nigeria repairs the mechanics of trade itself, the country will remain trapped in a cycle where every policy meant to restore confidence ends up constraining it further.