Kenya’s Sh337bn Dam Bet: Who Wins If High Grand Falls Returns?

Kenya is reviving the Sh337–340bn High Grand Falls dam (500–700 MW) after July’s PPP collapse. If bankable, it could cut system costs and lift KEGN/KPLC, cement names and banks—once procurement, hydrology and financing clear. Until then, it’s an option, not FID.

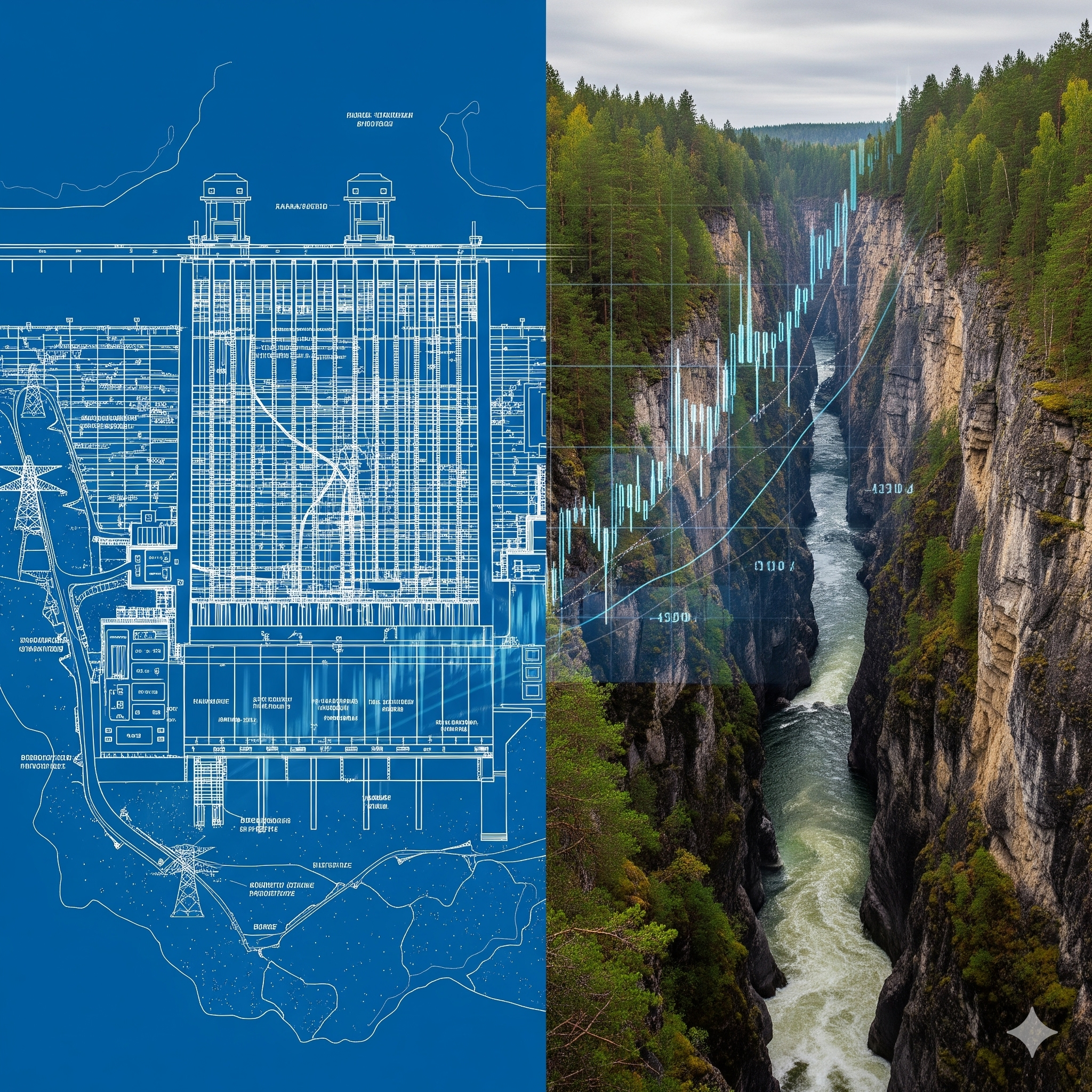

Kenya just reopened the book on High Grand Falls (HGF) — a Sh337–340 billion ($2.6–2.7 billion) multi-purpose hydro scheme on the Tana — days into the Olkaria Sustainable Energy Conference. The policy signal is unmistakable: after the National Treasury terminated the prior PPP on July 2, 2025 for a failed evaluation under Section 43(11)(c) of the PPP Act, the state is now framing a clean reboot, with capacity guidance oscillating between ~500 MW (conference brief) and ~700 MW (official and trade coverage). Either way, HGF would sit among East Africa’s largest new baseload assets, impounding roughly 5.6 billion m³ and reshaping Kenya’s seasonal merit order if it moves from headline to bankable structure.

Markets should care because the revenue and cost curves of several Nairobi-listed names hinge on three numbers. First, generation: 700 MW at a conservative 50% capacity factor yields ~3,066 GWh/year, versus 500 MW at 45% producing ~1,971 GWh/year. That delta is the difference between materially reducing thermal dispatch versus only denting it. For KenGen (NSE: KEGN), that scale defines whether HGF is an operator opportunity or simply an offtake adjacency; for Kenya Power (NSE: KPLC), it translates into system average cost pressure relief in wet years but heavier non-fuel pass-through from transmission and wheeling upgrades required to evacuate the new baseload. Cement makers like Bamburi (NSE: BAMB) and East African Portland (NSE: PORT) get multi-year volume uplift during the civil-works window; local lenders KCB Group (NSE: KCBG), Equity (NSE: EQTY) and Co-op (NSE: COOP) get fee income on advisory and syndication if a domestic tranche is carved out — but terming out 12–18 year paper will still lean on multilaterals and ECA cover. None of this prices in until procurement hygiene and financing clarity replace rhetoric.

The critical risk work is where the prior attempt failed. The July termination explicitly cited a failed evaluation report under the PPP Act, which implies the reboot must restart with fresh feasibility, updated E&S baselines, and a procurement rerun that is defensible to audit. If the state again tries to shoehorn a privately initiated proposal without robust competition, investors should expect longer timelines and higher risk premia in the PPA. The revival narrative also distances itself from the scrapped GBM/RCP pairing; that clears the cap table but raises a second-order risk: if a new EPC/developer consortium cannot evidence creditworthy equity and debt at term-sheet stage, the project will stall at MoU. Treat the “revive” headline as an intent signal, not FID.

Hydrology is the swing factor that turns a trophy dam into either a tariff reducer or a stranded asset. Tana basin inflows are volatile; if realistic capacity factors settle 10–15 percentage points below optimistic decks (say, 35–45% instead of 50–60%), levelized cost rises, and KPLC’s system cost savings shrink. Sediment load and reservoir management affect lifetime O&M and effective head; the promise of 5.6bn m³ storage is meaningful for irrigation and flood control, but it complicates operating rules that maximize power. The state’s messaging around 700 MW/KE Sh340bn resonates with climate-finance narratives, yet the bankable path will require blending concessional climate/SDG windows with ECA-backed EPC debt to keep end-user tariff paths politically tolerable.

Positioning, as an analyst, is to watch for three de-risking milestones before underwriting earnings impact. One: documents. A new RFQ/RFP with transparent scoring, plus publication of updated feasibility and ESIA, would cure the July deficiencies; absence of these within weeks of the conference would signal headline risk. Two: offtake and grid. A draft PPA (or operator mandate) that shows tariff structure, deemed-energy clauses, and curtailment rules, alongside a transmission plan for evacuation, determines how KEGN and KPLC cash flows are actually affected. Three: financing proof. Named lenders with indicated tickets and an indicative blended rate say far more than generic “development partner” language. Only when these surface should you model KEGN capex scheduling, KPLC pass-throughs, cement order books, and bank NII/NFIs. Until then, the right trade is a watchlist: KEGN/KPLC for disclosure cadence; BAMB/PORT for order-backlog hints; KCBG/EQTY/COOP for mandates; and policy risk priced via sovereign curves in case the model tilts from PPP to sovereign-backed EPC.

Contextually, this isn’t happening in a vacuum. With Ethiopia’s GERD now operational at multi-gigawatt scale, East Africa’s hydro race is real, and HGF could make Kenya more resilient in dry seasons while boosting cross-border trade in wet ones. But competitive pressure is not a substitute for governance discipline. The previous PPP process broke on evaluation quality; the market will reward evidence that the government learned from that failure. Until then, mark HGF as a medium-probability, long-dated option on Kenya’s baseload mix — valuable if it clears procurement, hydrology, and financing hurdles, immaterial to near-term earnings if it does not.