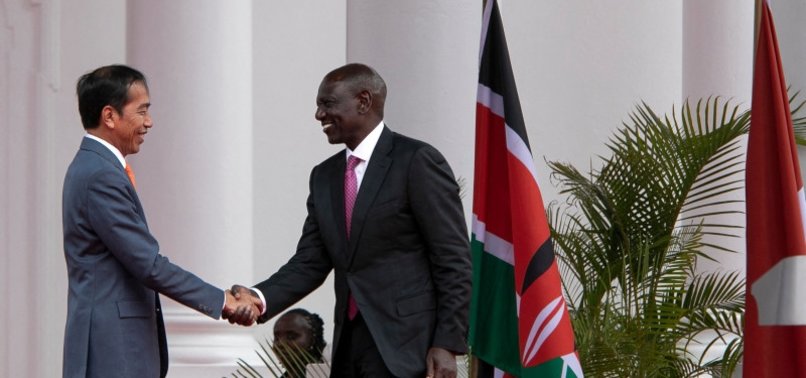

IndoNEX Anchors Kenya Indonesia Partnership

Kenya links with Indonesia ahead of IndoNEX 2025; USDKES=X volatility could compress as flows diversify while Indonesian risk appetite tracks ^JKSE and EIDO, signaling potential FDI into Kenya’s manufacturing and renewable energy chains.

Kenya’s deepening engagement with Indonesia ahead of IndoNEX 2025 signals a deliberate eastward rebalancing of supply chains, trade finance, and foreign direct investment. Two-way flows exceeded $600 million in 2023, up from roughly $450 million in 2020, dominated by Indonesian exports of palm oil, refined fuels, steel inputs, paper, chemicals, and fertilizers.

Kenyan shipments remain small—tea, coffee, soda ash, and floriculture together contribute well under $10 million—underscoring the asymmetry and the scope for export development. The policy intent is clear: diversify input sources, compress landed costs for food and industry, and link domestic manufacturing to Asia’s production networks to reduce dependence on legacy corridors.

Mechanics now align on both sides. Kenya’s Bottom-Up Economic Transformation Agenda prioritises import substitution, agro-industrial processing, and light manufacturing; Indonesia’s outbound strategy leverages its RCEP position to extend Asian value chains into Africa. Lower non-tariff friction, standardized product specifications, and expanded trade-credit lines from Indonesian banks compress transaction costs and delivery risk.

For Kenya’s tradables sector—about 22% of GDP—cheaper intermediates can cut input bills by 3–5%, lifting operating margins and improving export parity into EAC and COMESA markets. Energy linkages matter: stable palm-based feedstocks and refined products can smooth domestic price volatility and diversify away from single-region exposure.

The macro signal is direction over magnitude. With nominal GDP near $115 billion in 2025, lifting bilateral trade to $1.0–1.2 billion by 2026–2027 would add roughly 0.2% of GDP in net export gains if sourcing and re-exports scale as planned. Composition effects are more important than the headline. A two-percentage-point decline in imported input inflation for food processing and packaging reduces working-capital needs and shortens cash-conversion cycles for listed consumer, logistics, and packaging names.

On external balances, broader FX counterparties marginally support the shilling by smoothing seasonal USD demand. Reserves near $7.1 billion—about 3.8 months of import cover—remain sensitive to energy price swings, but longer-dated supplier credit from Indonesian firms can flatten the near-term hard-currency call and reduce rollover risk in trade finance.

Markets will price the corridor through currency, equities, and FDI channels. A wider Asia link can modestly compress USDKES=X volatility if documentary collections and supplier credit extend average payment tenors and diversify settlement currencies. Equity sentiment should improve first in logistics, warehousing, ports, and packaging as container throughput and inventory turns rise; valuation durability will depend on throughput elasticity to lower landed costs.

Outward FDI from Indonesia into Africa has surpassed $2 billion cumulatively; a Kenyan foothold in industrial parks and renewables could redirect a share into geothermal, grid equipment, and assembly for battery-adjacent components that marry Indonesia’s nickel ecosystem with Kenya’s renewable power base. Jakarta’s equity proxy (^JKSE) and offshore vehicles such as EIDO provide liquid gauges of Indonesian corporate risk appetite for such expansion.

Execution risk is non-trivial and will determine whether the initiative moves beyond signalling. Port and rail capacity, customs timelines, and standards harmonization must improve or price advantages will dissipate in logistics friction. Kenya’s cost of capital remains high in real terms; if term funding does not lengthen, manufacturers will capture only a fraction of the input-cost dividend. For Indonesia, partner risk includes policy drift and sub-scale production runs that undermine minimum efficient scale. Absent a bilateral investment treaty with enforceable protections, dispute resolution and intellectual-property safeguards may lag commercial intent, lifting hurdle rates and slowing project approvals.

The geopolitical overlay favours diversification. A Kenya–Indonesia axis complements China’s established footprint while reducing single-partner dependency and broadening political-risk diversification. It fits a south-south industrial policy template that prioritizes process technology, equipment standards, and vocational training alongside merchandise trade.

If joint ventures reach financial close in utility-scale renewables and industrial equipment, Kenya’s FDI mix tilts away from concessional debt toward equity-like inflows, easing pressure on a public-debt ratio in the mid-60s percent of GDP and improving the interest-growth differential through a shift in financing composition.

The outlook is verifiable on a defined timetable. By December 2026, bilateral trade should exceed $1.0 billion, the number of Indonesian firms operating or exhibiting in Kenya should at least double from current levels, and one utility-scale energy or manufacturing project should reach financial close.

Concurrently, a one to two-percentage-point reduction in average landed costs for key intermediates and a 10% rise in Kenya’s exports to Asia would confirm that the corridor is transmitting real value. If these markers fail to materialize, IndoNEX will read as diplomatic theatre; if they land, the initiative marks a durable shift in Kenya’s external integration.