Ethiopia’s GERD: From Water Flows to Bond Spreads

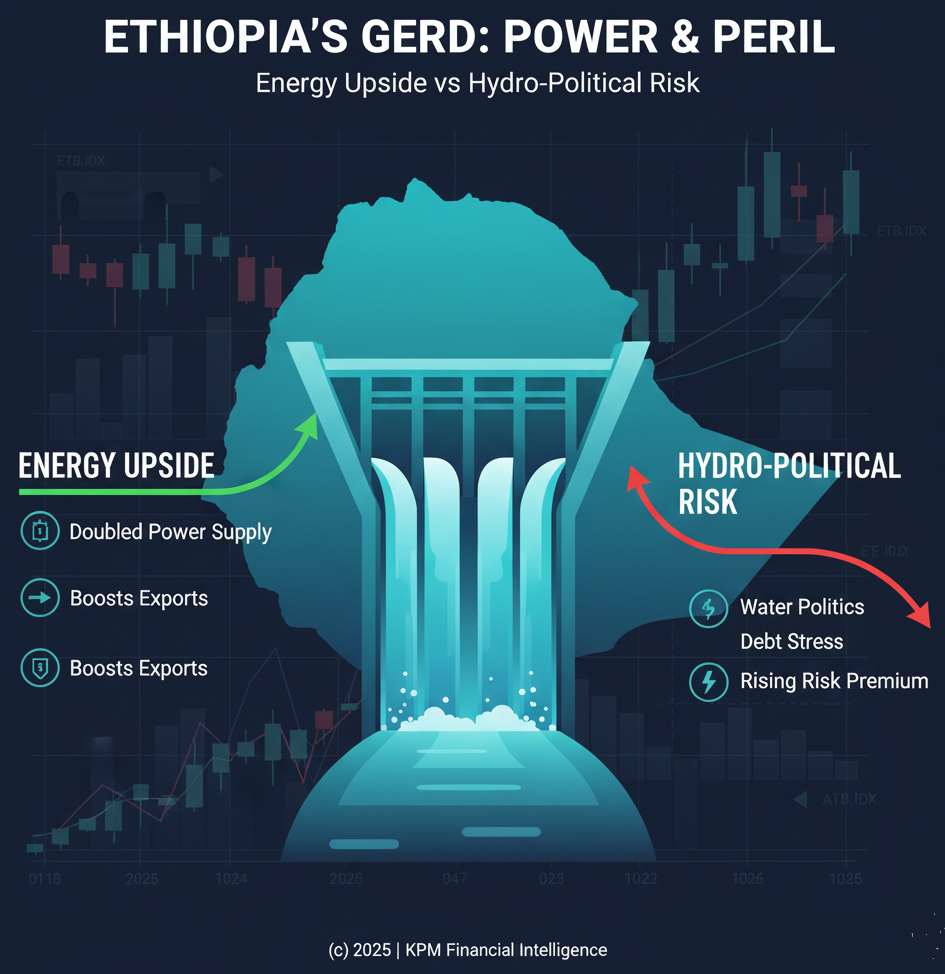

Ethiopia’s GERD doubles power supply, boosts exports, and reshapes Africa’s bond markets. Investors must weigh energy upside against water politics, debt stress, and a rising hydro-political risk premium.

Africa’s biggest dam may soon test bond markets as much as it tests the Nile. The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD), inaugurated in September 2025, delivers more than 5,000 megawatts of renewable power, more than doubling Ethiopia’s electricity supply. At a cost of roughly USD 5 billion, financed largely from domestic bonds and public contributions, it is one of the few African megaprojects built without heavy reliance on China or multilaterals. For Ethiopia, it is celebrated as a development milestone. For Egypt and Sudan, it is feared as a potential trigger for water insecurity. And for investors, it may be the start of a new chapter where hydro-politics spill directly into capital markets.

Much of the analysis so far has focused on how the dam alters river flows and crop yields. Hydrologists have modelled different filling scenarios, showing how Egypt could face losses of up to half its annual Blue Nile inflows under aggressive timelines, while economists have argued that Sudan might gain nearly USD 30 billion in long-run GDP if cooperation prevails. A few studies even suggest GERD could yield a negative net present value under pessimistic assumptions about drought and weak power exports. These findings matter for governments, but they leave investors with unanswered questions. Bondholders and foreign direct investors do not buy models of hectares irrigated; they buy exposure to spreads, reserves, and cashflows. And on those fronts, the debate has been surprisingly thin.

For Ethiopia, GERD is both a source of strength and a point of vulnerability. By displacing expensive diesel imports, it could save hundreds of millions of dollars a year, offering relief to foreign reserves that currently cover less than three months of imports. Power exports to Sudan, Djibouti, and Kenya could generate upwards of half a billion dollars annually in hard currency, a meaningful cushion for an economy where FDI inflows struggle to cross USD 3 billion a year. Cheap, reliable energy also positions Ethiopia’s industrial parks as magnets for energy-intensive investment in textiles, cement, and agro-processing. Every megawatt sold abroad is not only a unit of power but also a hedge against the country’s chronic FX drought.

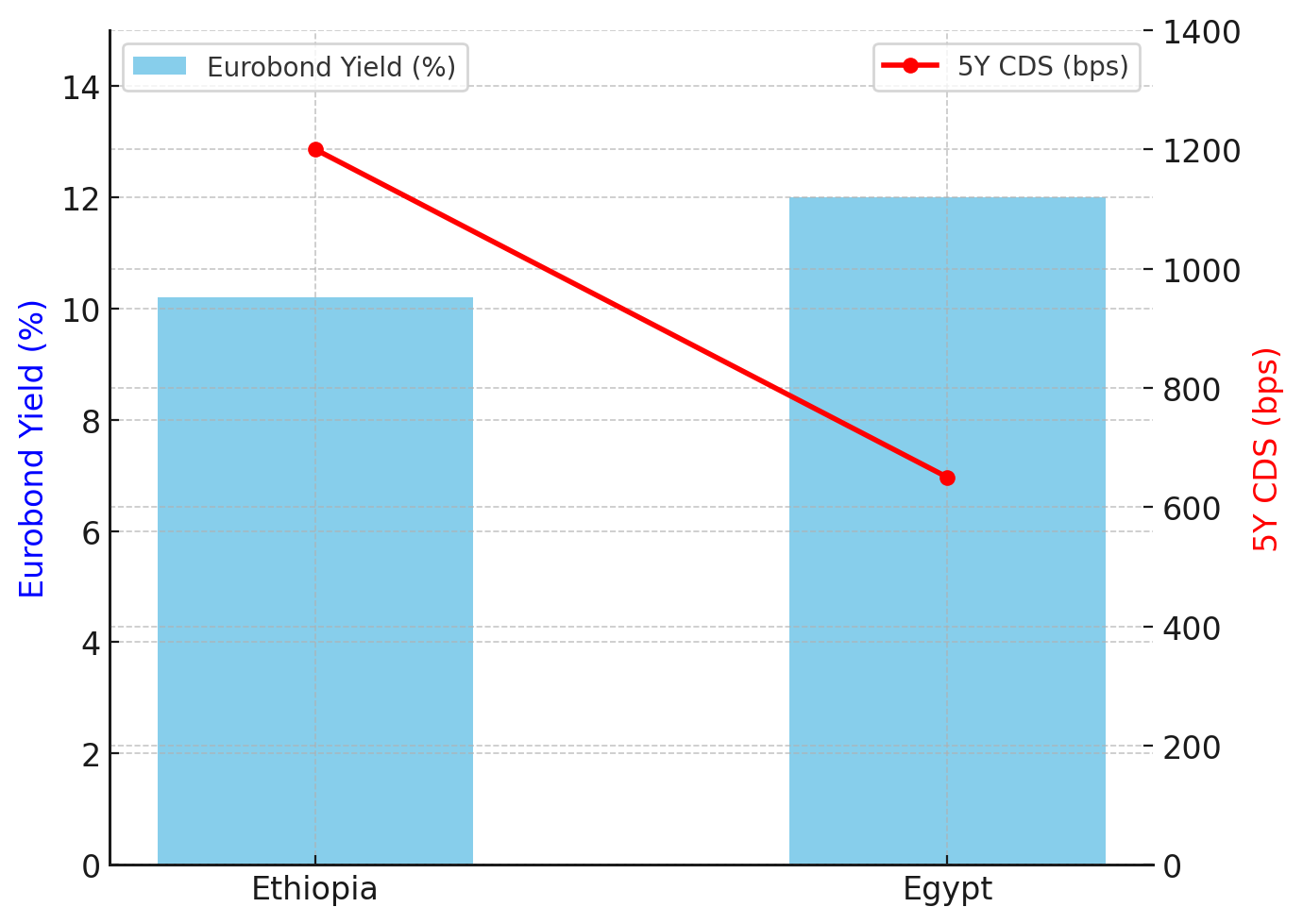

Yet optimism is tempered by market realities. Ethiopia’s only outstanding Eurobond, the USD 1b 6.625% 12/2024 (Ticker: XS1196517434), restructured after the 2023 talks, continues to trade with implied yields above 10 percent, some 750 basis points over U.S. Treasuries (USGG10YR). Five-year CDS on Ethiopia (ETHIOPIA 5Y CDS SR, last quoted above 1,200 bps) reflects high default risk and limited investor confidence. A breakdown in diplomacy with Egypt could easily widen spreads by another 300 to 400 basis points, push the birr (ETB:CUR) further down its double-digit depreciation path, and unsettle investors considering long-term commitments.

Sudan, by contrast, stands to benefit if water flows are managed cooperatively. Agriculture accounts for nearly a third of its USD 34 billion GDP, and more predictable irrigation could improve yields while cheaper power imports lower costs. With no active Eurobond curve since its 2020 default, Sudan’s risks are visible instead in its volatile currency (SDG:CUR) and the scarcity of portfolio inflows. Egypt, meanwhile, faces the starkest challenge. Over 90 percent of its freshwater comes from the Nile, so any disruption cascades into agriculture, employment, and food security. Food imports already cost between USD 15 and 20 billion annually, and are directly exposed to global grain markets. Benchmark wheat futures (W 1 Comdty) have surged more than 30 percent since 2022, and corn (C 1 Comdty) remains elevated, adding further fiscal strain. With sovereign debt above 90 percent of GDP, Egypt’s Eurobonds, such as the USD 7.5% 2032 (Ticker: XS1803216319), yield around 12 percent, and its 5-year CDS (EGYPT CDS USD SR 5Y) trades above 650 bps. While much of this reflects inflation and fiscal pressure, Nile tensions could become an incremental driver of both yields and CDS spreads if disputes harden.

The regional context is illuminated by comparisons with other African megaprojects. Kenya’s Standard Gauge Railway, financed by Chinese loans, saddled Nairobi with debt and limited returns, weighing on the Kenya 6.875% 2027 Eurobond (XS1843436803). Mozambique’s LNG boom collapsed under insurgency, with the Mozambique 5% 2031 (XS1843436803) trading at distressed levels, CDS above 1,000 bps. Nigeria’s Mambilla hydro scheme remains stalled, another stranded megaproject. GERD is different: domestically financed, politically sovereign, and directly tied to export revenues. But this uniqueness exposes Ethiopia to scrutiny: without a foreign guarantor, the dam’s economics feed directly into sovereign credit risk.

For investors, three paths stand out. A cooperative scenario, in which Ethiopia secures export deals, Sudan benefits from stable flows, and Egypt adapts through efficiency and imports, could compress Ethiopia’s spreads by 150–200 basis points and push CDS tighter. A conflict scenario, where disputes escalate and security ties deteriorate, could widen spreads by 300–400 basis points, push CDS on both Ethiopia and Egypt higher, and trigger ratings downgrades. A climate stress scenario, marked by multi-year droughts, would curtail GERD’s exports, drain FX reserves, force birr devaluation, and risk restructuring of power purchase agreements. In each scenario, it is the market translation of hydro-politics — in bonds, CDS, and currencies — that matters most.

Beyond risk, GERD also offers an opportunity. Africa’s cumulative green bond issuance remains below USD 10 billion, dwarfed by over USD 4 trillion globally. GERD could be securitized into export-backed green bonds, opening channels to ESG investors. Egypt’s own 2020 Green Bond (XS2229196910) showed appetite exists; Ethiopia could extend that into renewable hydro, especially if Gulf sovereign wealth funds like ADIA and Saudi Arabia’s PIF or European pension funds seek exposure. The potential for GERD to become Africa’s first securitized hydro asset is real — if diplomacy holds.

The dam’s true significance lies not only in the electricity it generates but in the way it forces markets to rethink risk. For decades, Nile disputes were framed in hydrology and sovereignty. Now they will also be measured in basis points and CDS levels. The Hydro-political Risk Premium (HRP) may sound novel today, but just as the Strait of Hormuz shapes shipping insurance, Nile Basin tensions could soon shape bond yields and CDS spreads. Investors who price it intelligently could capture Ethiopia’s green upside. Those who ignore it risk being blindsided by the political undercurrents of the world’s longest river.