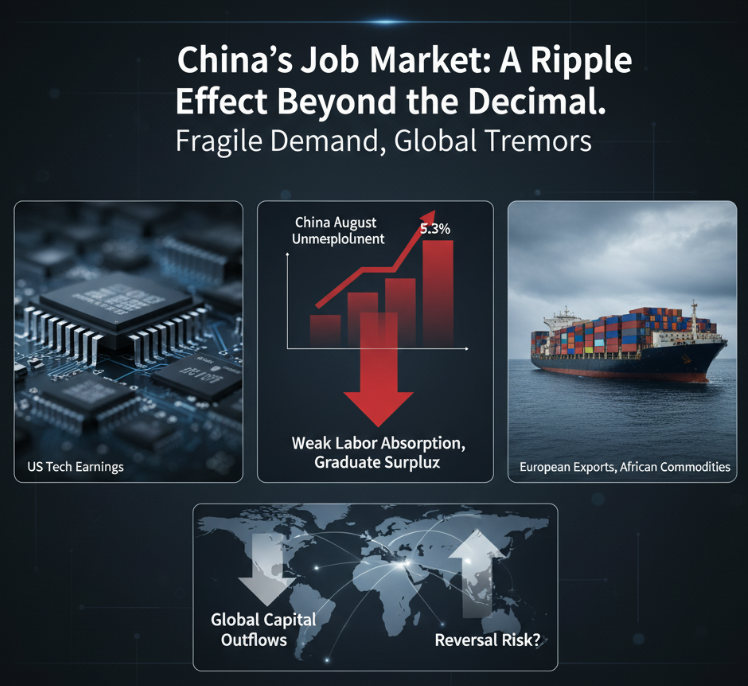

China’s Jobless Numbers Echo Beyond Beijing

China’s August unemployment edged up to 5.3%, but investors read more than a decimal: weak labor absorption, graduate surpluses, and structural mismatches signal fragile demand, with ripples across U.S. tech earnings, European exports, African commodities, and global capital flows.

On September 15, China’s National Bureau of Statistics reported that the country’s surveyed urban unemployment rate rose to 5.3 percent in August, up from 5.2 percent in July. In absolute terms, the move is barely perceptible. Yet in financial markets, such fractional changes often act as signals of underlying strain, prompting traders and analysts to reassess consumption patterns, capital flows, and the trajectory of the world’s second-largest economy. What looks like statistical noise in Beijing can ripple across equities, commodities, bond yields, and emerging-market currencies.

Domestically the dynamics are shaped by a predictable seasonal surge in labour supply: every summer millions of new graduates enter the workforce, tightening conditions and nudging joblessness upward. This year the influx was especially heavy, with 12.22 million new graduates compared with about 11.79 million a year earlier. That surge alone helps account for the August rise, but the deeper story is structural. China is trying to shift its growth model toward services, green sectors, high tech, and consumption-led growth, yet many of its graduates remain trained for industries where demand is flattening. The mismatch between what the labour force offers and the jobs available is leaving an increasing share of educated youth either unemployed or underemployed, eroding confidence that is critical for domestic consumption — China’s hoped-for engine of future growth.

Markets interpreted the unemployment figures and related weak data through multiple channels. In Asia, equity markets opened cautiously and bond yields showed mixed signals, reflecting investors’ unease about growth momentum. U.S. futures traded flat as investors weighed whether the labour data was a statistical blip or a more durable warning sign. Bond markets were quicker to react: U.S. 10-year Treasury yields (US10Y) slipped toward five-month lows, signalling a flight to safety and reinforcing expectations that slower global demand could ease inflationary pressures. In China itself, 10-year government bond yields (CN10Y) ticked higher, reflecting investor caution about fiscal and credit risks as Beijing juggles growth support with debt sustainability.

For the United States, the corporate exposure is obvious. Apple (AAPL), Tesla (TSLA), and Nvidia (NVDA) all rely heavily on Chinese consumers, and weaker labour absorption threatens discretionary spending. Beyond corporate earnings, the macro channel is equally important: weaker Chinese demand reduces pressure on goods prices, indirectly supporting the Federal Reserve’s disinflationary efforts. That paradox — weaker Chinese households helping U.S. households through softer import prices — is part of the interconnected logic of markets.

Europe’s position is more conflicted. German automakers such as Volkswagen (VOW3.DE) and BMW (BMW.DE), French luxury houses like LVMH (MC.PA) and Kering (KER.PA), and Italian exporters remain deeply reliant on Chinese demand, and signs of labour market fragility cast doubt over their forward sales. Yet there is a counterweight: weaker Chinese consumption tends to ease energy demand, nudging down Brent crude (LCOc1) and Dutch TTF gas (TTF=F). That can provide temporary relief for European households and soften inflation, but it does not offset the damage to export-oriented industries. For the European Central Bank, the combination of slowing external demand and easing price pressures complicates the policy calculus.

Africa absorbs the shock most directly through the commodity channel. Copper (HG=F), iron ore (SCO:COM), and platinum (PL=F) are priced on global exchanges but driven by Chinese demand expectations. A jobs report in Beijing that hints at weaker factories or cautious households quickly translates into pressure on export revenues, fiscal positions, and currencies. The rand (USD/ZAR), the naira (USD/NGN), and the kwacha (USD/ZMW) typically weaken against the dollar when Chinese data falters. Beyond trade, the investment dimension is equally sensitive: if Beijing reallocates resources inward to stabilise its domestic economy, Belt and Road financing could slow, tightening Africa’s infrastructure pipeline and amplifying debt vulnerabilities.

Markets therefore watch even the smallest change with disproportionate attention. A tenth of a percentage point increase in unemployment is trivial statistically but meaningful directionally. If Beijing cannot contain joblessness despite repeated policy pledges, investors see a warning sign that structural rigidities remain unresolved. Equity traders cut back on China-exposed names, commodity desks trim demand forecasts, and foreign-exchange markets strengthen the dollar against the yuan (USD/CNH) and other emerging-market currencies.

The policy response will determine whether August’s rise proves fleeting or a harbinger of deeper trouble. Training schemes and subsidies may temporarily steady the numbers but cannot resolve the structural mismatch between graduate skills and high-productivity employment. A larger fiscal push targeting housing, infrastructure, or green industries could restore short-term confidence, but at the cost of adding new layers of debt to a system already stretched. Markets know that China cannot indefinitely paper over structural weaknesses, which is why even minor labour data shifts reverberate so widely.

The September 15 release underscores how entwined China’s domestic conditions are with global financial flows. What appears to be a small adjustment in Beijing has the power to reset expectations in Wall Street earnings, Frankfurt’s export outlook, and Johannesburg’s currency markets. The unemployment rate has become more than a measure of labour absorption; it is the global economy’s pressure valve, a barometer of consumption strength, industrial demand, and policy resolve. In an environment where sentiment pivots on fragile signals, a tenth of a point in China can be enough to redirect capital across the world.