Cape Verde’s Coin Shortage Exposes a Micro-Liquidity Breakdown

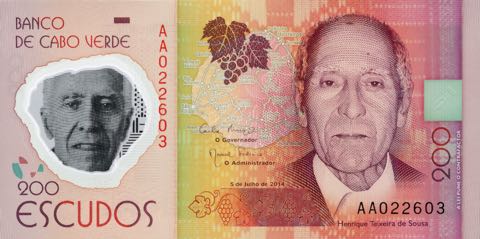

Despite BCV’s injection of 1.4M coins (≈ CVE 140M / USD 1.3M), Cape Verde’s markets still face severe small-change shortages. Escudo (EUR/CVE: CVE=) stability masks a deeper liquidity gap—money exists on paper, not in people’s hands.

In Praia’s bustling Plateau and Sucupira markets, the clang of escudo coins has grown faint. Vendors and customers alike report the same frustration — there is simply no change. Despite the Bank of Cabo Verde (BCV) announcing that 1.4 million coins (≈ CVE 140 million / USD 1.3 million) were introduced between July and September 2025, daily trade remains paralyzed by what locals now call a “currency drought.” It’s not that money isn’t being printed — it’s that it’s not circulating where it matters.

The episode has become a case study in how monetary policy can fail at the point of transaction. BCV’s injection was meant to replenish coin liquidity and restore normal retail operations. Yet, on the ground, vendors say the opposite has occurred: coins worth CVE 100 or less have vanished from circulation, forcing sellers to hand out candy or soft drinks as substitutes for change. The paradox illustrates a growing disconnect between monetary supply and monetary velocity — a warning sign for frontier economies whose cash ecosystems remain fragile even under macro stability.

According to BCV’s monetary report for Q2 2025, M1 money supply grew by roughly 4 percent year-on-year, while inflation stayed contained around 2.1 percent, and the policy rate held steady at 2.50 percent (CBVIR: 2.5%). By those metrics, liquidity should be abundant. But coins are not macro liquidity — they are microeconomic trust. Once small denominations disappear into household jars, retail tills, or transport floats, they stop functioning as instruments of exchange. Economists call this phenomenon denomination stickiness, seen before during Nigeria’s 2023 naira redesign crisis (USD/NGN: NGN=1,600) and Kenya’s 2018 note withdrawal (USD/KES: KES=129.4), when cash velocity fell sharply as citizens hoarded usable currency.

In Cape Verde’s case, the symptoms reveal a deeper monetary-transmission gap. Coins may have reached commercial banks, but distribution through branch networks into informal markets appears broken. The BCV’s logistics infrastructure — reliant on scheduled deliveries via national carriers and bank intermediaries — often bypasses small traders who operate outside formal banking channels. The result is a liquidity trap at the base of the economy, where demand for change exceeds both physical supply and institutional responsiveness.

That distortion has macro consequences. With roughly one-third of Cape Verde’s workforce employed in informal trade and services, a slowdown in petty-cash transactions translates into lower consumption at scale. Market vendors told Inforpress that sales volumes have fallen by as much as 20 percent since midyear, as buyers abandon purchases when change isn’t available. The impact on GDP may appear marginal — perhaps a 0.2–0.3 percentage point drag — but the signal it sends about financial inclusion is far more consequential.

The situation also underscores the fragility of cash logistics in small island economies. Unlike mainland African states with dense banking corridors, Cape Verde’s 10-island geography imposes a high logistical premium on cash movement. BCV’s replenishment schedules often face shipping delays and security constraints, resulting in uneven distribution between urban and rural markets. A structural solution may require deploying digital micro-payments platforms such as Mobi.CV or Unitel T+, whose transaction fees under CVE 500 (≈ USD 4.5) could absorb low-value sales currently constrained by coin scarcity.

For international investors, this episode mirrors a wider concern: monetary inclusion as a determinant of macro credibility. Frontier-market risk models often focus on debt ratios and reserves, yet micro-liquidity dysfunctions can signal deeper institutional weaknesses. Cape Verde’s public debt, at 55 percent of GDP, remains moderate; external debt—mostly concessional—sits around 41 percent, largely financed by the IMF (SDR: XDR), World Bank (NYSE: WBG), and African Development Bank (XBRU: AFDB). Still, if transactional frictions persist, they can erode consumer confidence, weaken local commerce, and delay tax revenue collection, feeding back into fiscal strain.

The irony is that Cape Verde’s fundamentals remain among the region’s most stable. The escudo (EUR/CVE: CVE=) is pegged to the euro (EUR/USD: EUR=1.09) under an IMF-supported arrangement, insulating the economy from exchange-rate volatility that has hammered peers like Ghana (USD/GHS: GHS=15.2) or Nigeria (USD/NGN: NGN=1,600). Tourism receipts cover roughly 30 percent of GDP, remittances account for 12 percent, and the current account remains close to balance. Yet even with this stability, the coin crisis demonstrates how a well-managed economy can still stumble on the smallest link in the liquidity chain.

If BCV fails to normalize circulation swiftly, secondary effects could surface. Retailers may round prices upward to compensate for lack of change, generating localized inflation drift. Informal credit between vendors could rise, fragmenting payment discipline. Over time, citizens may shift entirely toward mobile money — already representing 14 percent of total retail transactions — bypassing cash altogether. This could accelerate digitization, but at the cost of excluding those without access to mobile services—currently about 20 percent of adults.

The policy remedy is not more coins—it’s better distribution. BCV could mandate that commercial banks maintain minimum small-change inventories, offer incentives for coin recirculation, or use postal and telecom networks for redistribution. Public awareness campaigns, coupled with transparent regional allocation data, would help restore confidence that monetary supply matches on-the-ground experience.

In global terms, Praia’s coin shortage is a reminder that monetary credibility starts at street level. It doesn’t matter how sound your GDP or inflation numbers look if a vendor can’t make change. In the mechanics of trust that define every economy—from Wall Street to West Africa—sometimes the smallest denominations carry the biggest signal.