Cameroon’s Hidden Trade Corridor Fuels Growth but Erodes Fiscal Reach

Cameroon’s informal exports to Chad and Nigeria hit CFA 108.8B (≈ USD 180M), bypassing customs and distorting fiscal data. With XAF stability masking structural gaps, the flows reveal how trade thrives beyond BEAC control yet weakens tax revenue and policy reach.

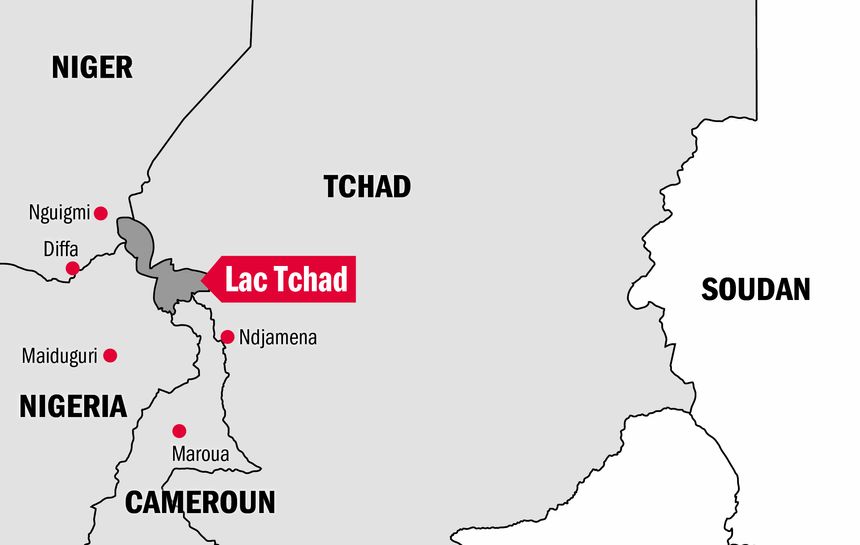

Cameroon’s informal export network to Chad and Nigeria is revealing both the resilience and the structural limits of the Central African economy. According to data from the 2024 Informal Cross-Border Trade Survey released by the National Institute of Statistics (INS) in mid-2025, informal exports to Chad and Nigeria reached about 108.8 billion CFA francs (≈ USD 180 million), roughly 1–1.5 percent of GDP. These flows—mostly agricultural goods, livestock, and textiles—are unrecorded in the official current-account balance, yet they anchor livelihoods across the northern trade corridors linking Maroua, Kousseri, Ekok-Mfum, and Bamenda-Enugu.

The phenomenon illustrates the paradox of economic integration without formalization. While Cameroon’s formal exports are tracked through the Douala Port Authority and large corporates such as BGFI Bank Group (Libreville-based) and UBA Nigeria (NGX: UBA), the vast unmonetized flow of goods bypasses customs entirely. This denies the state revenue, complicates monetary management for the Bank of Central African States (BEAC), and weakens trade statistics used for fiscal planning. The INS data show that the informal volume is small relative to formal cocoa and timber exports, which together exceed USD 1 billion annually, but the flows remain decisive for household liquidity and regional consumption.

The trade composition skews heavily toward primary goods—onions, maize, cattle, palm oil, and re-exported manufactured items from Nigeria. Roughly 70 percent of transactions occur in cash, denominated in CFA (XAF) and naira (NGN). This dual-currency ecosystem distorts BEAC’s liquidity control. Although the euro peg provides nominal stability, untracked cross-border cash circulation erodes the transmission of monetary policy. Nigeria’s FX restrictions and the wide parallel-market premium (USD/NGN ≈ 1,600) further incentivize barter and informal settlement, embedding structural inefficiency in regional trade.

Institutional weaknesses compound the problem. Cameroon’s tax-to-GDP ratio hovers near 13 percent—below the sub-Saharan Africa average of 16 percent—leaving limited room to finance social programs. The loss of customs revenue through informal exports could amount to 0.3–0.5 percent of GDP annually. For a budget already strained by rising security expenditures in the Far North and infrastructure commitments ahead of the 2026 African Nations Championship, such leakages matter. They also distort fiscal equalization between formal export hubs and peripheral regions where trade taxes are chronically under-collected.

Multilateral institutions including the World Bank and African Development Bank have flagged this pattern as a hidden drag on regional convergence within the Central African Economic and Monetary Community (CEMAC). Despite macro stability—CFA franc inflation ≈ 3.6 percent, public debt ≈ 48 percent of GDP, and 10-year government yields near 5.8 percent (GOVCMR10Y)—Cameroon’s productive frontier remains narrow. Informal trade, by substituting for formal export channels, reduces the country’s ability to capture external financing. With foreign direct investment inflows at only USD 0.9 billion in 2024 and portfolio holdings minimal, the lack of transparent trade data raises the sovereign-risk premium embedded in instruments such as Cameroon’s 2032 Eurobond (ISIN XS2433902114, ≈ 8.7 percent YTM).

Regional comparisons highlight the opportunity cost. Ghana’s integration with ECOWAS markets, supported by digital customs monitoring, lifted its recorded nontraditional exports by 12 percent in 2024. Kenya’s implementation of the Integrated Customs Management System (ICMS) cut border losses by half within two years. In contrast, Cameroon still depends on manual reporting across key crossings, leaving large valuation gaps between domestic production data and recorded exports. These inconsistencies complicate macro surveillance by the IMF and erode the accuracy of balance-of-payments projections underpinning fiscal-deficit targets (3.5 percent of GDP in 2025).

There are signs of policy adaptation. The Ministry of Finance has initiated pilot e-declaration programs at Garoua-Boulaï and Kousseri with technical support from the European Union, aiming to register small traders and offer simplified tax identification numbers. Success would depend on whether the government can integrate informal traders into digital-payment ecosystems, potentially through mobile-money partnerships with MTN Group (JSE: MTN) and Orange (EPA: ORA). Digitization could accelerate financial inclusion while creating a transparent data trail for cross-border transactions—precisely the infrastructure required to attract blended-finance and ESG-linked investment.

Yet, the broader challenge remains political economy. Informal trade networks often coexist with entrenched patronage systems that benefit from opacity. Efforts to formalize risk resistance from intermediaries who profit from arbitrage between official and unofficial exchange rates. Without clear incentives—such as lower tariff rates, tax credits, or simplified customs processes—formalization may stall despite technological readiness.

For investors, the implications are twofold. On one hand, the persistence of informal exports sustains local consumption and limits unemployment shocks, stabilizing Cameroon’s internal demand base. On the other, it signals underdeveloped fiscal capacity, complicating sovereign-debt sustainability metrics used by global funds such as the iShares J.P. Morgan EM Bond ETF (NASDAQ: EMB). The country’s ability to translate regional trade into taxable value will determine whether it remains a mid-tier frontier credit or progresses toward an investable emerging-market profile.

Cameroon’s unrecorded exports to Chad and Nigeria are thus not just a footnote to regional trade—they are an efficiency paradox that exposes both the adaptability of markets and the fragility of state capacity. The flows moving silently across informal corridors may be small in value but large in signal: they quantify the distance between economic activity and institutional reach in one of Central Africa’s most strategically positioned economies.