Burkina Faso’s Visa Gamble Tests Africa’s Capital Markets

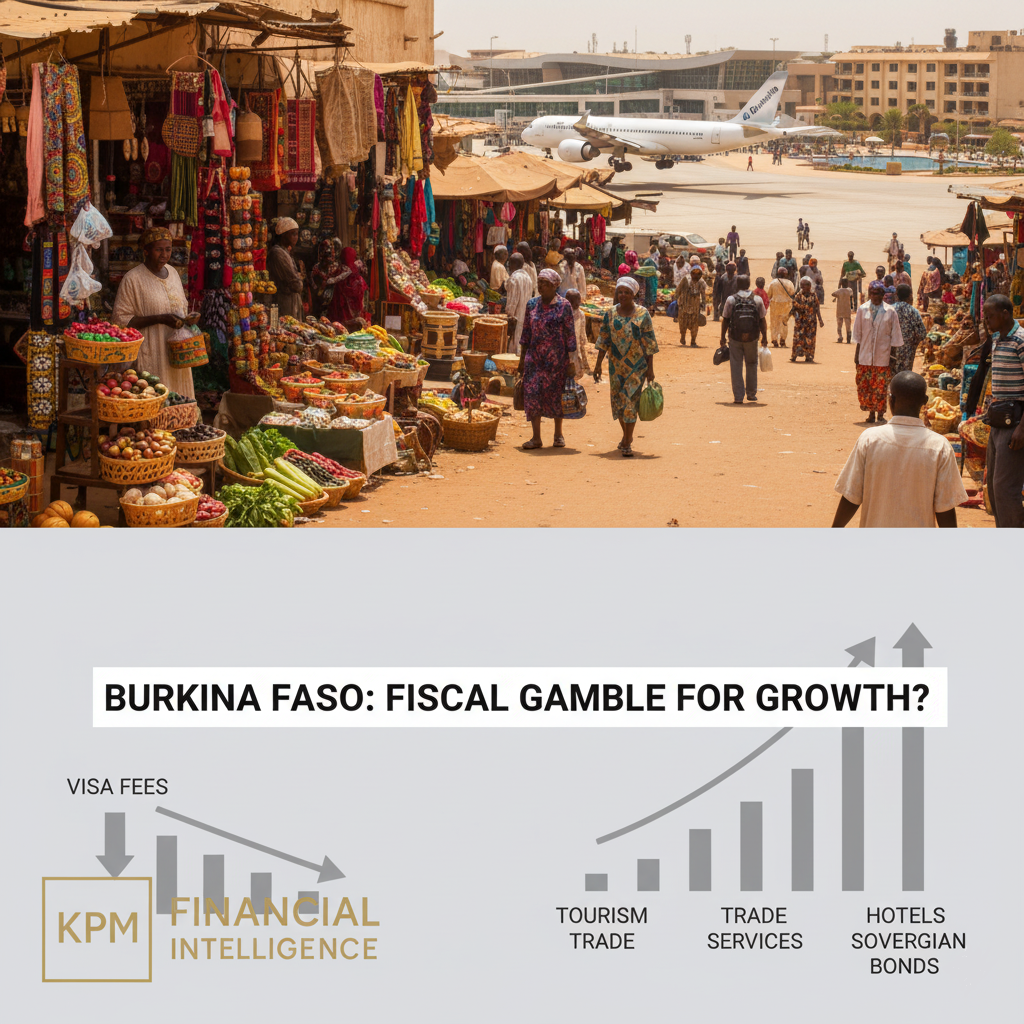

Burkina Faso’s move to scrap visa fees for all African travelers is more than symbolism. It is a fiscal gamble that swaps steady fee income for the hope of higher tourism, trade and service revenues—one that investors will track for its ripple effects across airlines, hotels and sovereign bonds.

Burkina Faso’s decision last week to scrap visa fees for all African travelers may appear at first glance to be a symbolic act of pan-African solidarity. In reality, it is a calculated fiscal gamble with implications that stretch beyond its borders into the economics of tourism, the balance of payments and the way investors price African sovereign and corporate risk.

Visa charges, usually between $50 and $100, have long provided African governments with a modest but predictable stream of non-tax revenue. In Burkina Faso’s case, as many as 50,000 African visitors each year may have contributed roughly $3.5mn in fees. Removing that line item creates an immediate hole in the fiscal accounts of a country already under pressure from high security and social spending. The wager is that the multiplier effect of higher travel volumes will more than compensate for the loss. If arrivals rise by 20 per cent and each additional visitor spends $500 in-country, the foregone $3.5mn could be eclipsed by more than $5mn in new foreign exchange receipts. With 15–18 per cent of that spending captured through VAT, hotel levies and income tax, the fiscal balance could even tilt back into surplus.

The key question is whether African travelers are as price-sensitive as policymakers assume. Experience elsewhere suggests they are. Studies in East Africa show that every dollar waived in visa charges can generate five to ten dollars in downstream spending. Rwanda’s liberal visa policy has been instrumental in cementing its position as a regional conference hub, with foreign exchange gains far outweighing the fees sacrificed. Investors in RwandAir (private but expanding codeshares with Qatar Airways [QATAR.UD]) and Kigali International Airport concession debt have watched this model closely. Burkina Faso is not yet a major tourist draw, and as a landlocked, resource-dependent state its attractions are different, but by lowering entry costs it seeks to reposition itself competitively against neighbours that retain visa barriers. Conferences, cultural events and regional business travel are attainable entry points that could deliver incremental foreign exchange and provide a measure of fiscal relief.

The consequences will not be confined to the treasury. Airlines and airports stand to benefit from higher passenger numbers and throughput. Listed carriers such as Ethiopian Airlines (ETHA.OL, via bond programme), Kenya Airways [KQNA.NR], and South African Airways’ restructuring-linked entities are all sensitive to incremental intra-African traffic. Every additional traveller generates not only ticket revenue but also ancillary charges, fuel uplift and retail spend in terminals. For concessionaires like Aéroports de Paris [ADP.PA], which has equity interests in multiple African hubs, and for pan-African hotel operators like City Lodge Hotels [CLH.J] and Tsogo Sun Hotels [TGO.J], incremental arrivals feed directly into earnings expectations. More broadly, a sustained increase in arrivals would appear in the services balance, strengthening the current account and providing marginal support to the currency and sovereign debt-service capacity. Such improvements are unlikely to transform Burkina Faso’s credit story overnight, but they could underpin modest spread compression in its eurobonds (BFAGR 2027 USD, trading wide in secondary markets).

The challenge, as investors know well, lies in execution. Visa fees are immediate and guaranteed, while tourism inflows are lagged and exposed to shocks. Digital application systems must operate reliably, border infrastructure must cope with higher volumes and political stability must hold if the revenue bet is to succeed. Without complementary investments in airports, digital processing and security, the fiscal sacrifice may outweigh the benefits. Markets will therefore watch high-frequency indicators closely. Monthly arrivals, hotel occupancy and average spend per visitor will reveal whether the demand response materializes, while cross-border card transactions from issuers such as Equity Group Holdings [EQTY.NR] and Standard Bank Group [SBK.J] will show whether the fiscal gap is being filled. If these trend positively over several quarters, the policy will begin to look less like symbolism and more like financial innovation.

For other African governments, the move raises a broader question: should mobility be treated as a fiscal lever rather than a diplomatic concession? Visa fee income is modest, while the upside from tourism, services and business travel can be much larger if supported by infrastructure and governance. A corridor-based approach, beginning with regional neighbors or key business partners, may provide a safer template. Coupled with transparent data publication, performance-linked airport concessions, and reinvestment in border systems, such initiatives could even be structured in ways that capital markets would reward.

Burkina Faso has effectively securitized goodwill. It has traded a predictable but low-yield cash stream for a riskier bet on traffic growth, services revenues and international branding. If the gamble pays off, it could reposition the country as a pioneer of openness at a time when many states are turning inward. If not, it will underline the fragility of fiscal experiments in security-stressed economies. Either way, the initiative deserves the close attention of investors, because in Africa’s frontier markets even small shifts in how people move can have outsized effects on how money does.