Africa’s Credit Deficit in the Age of China’s Tech Lending Boom

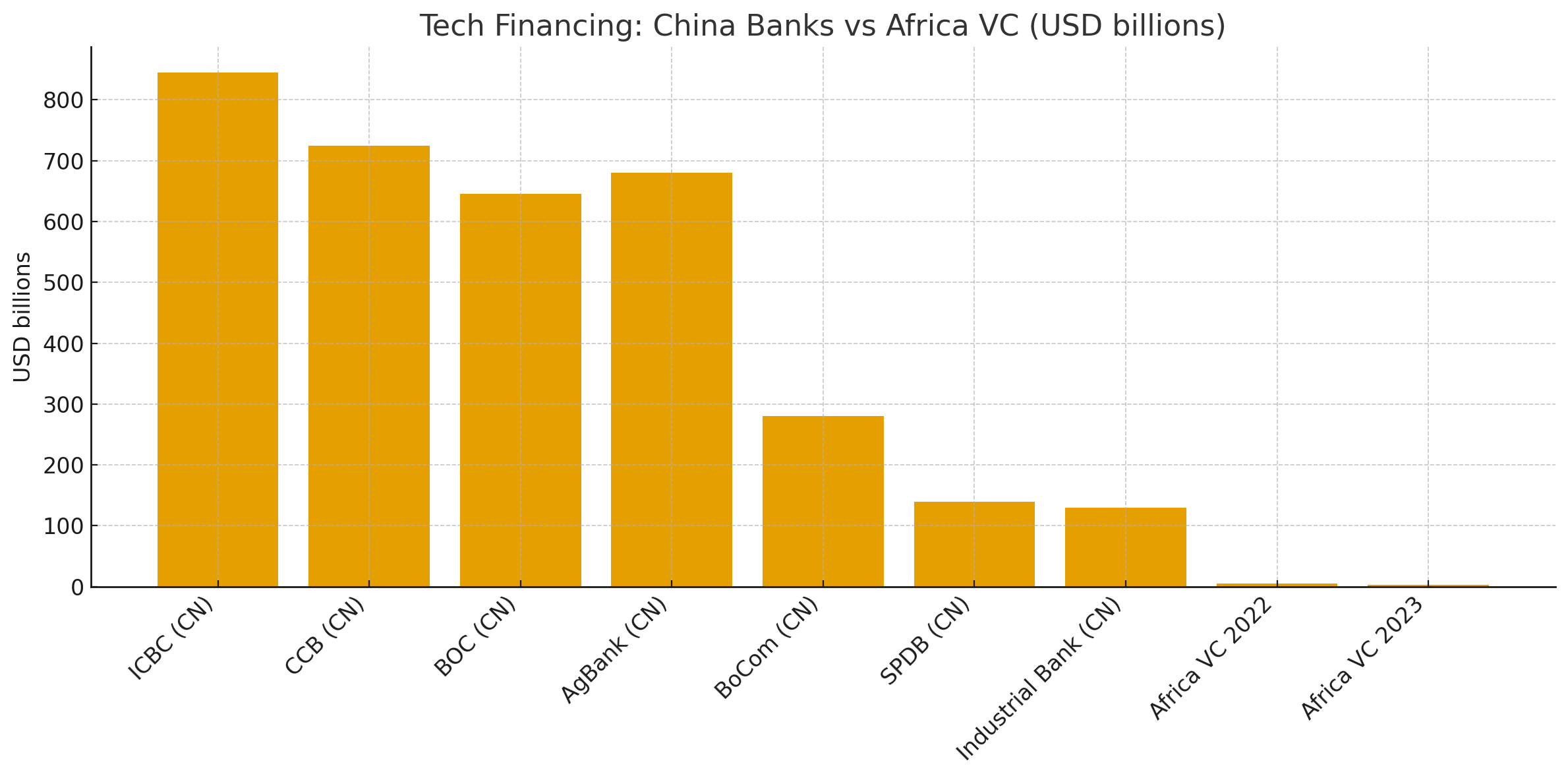

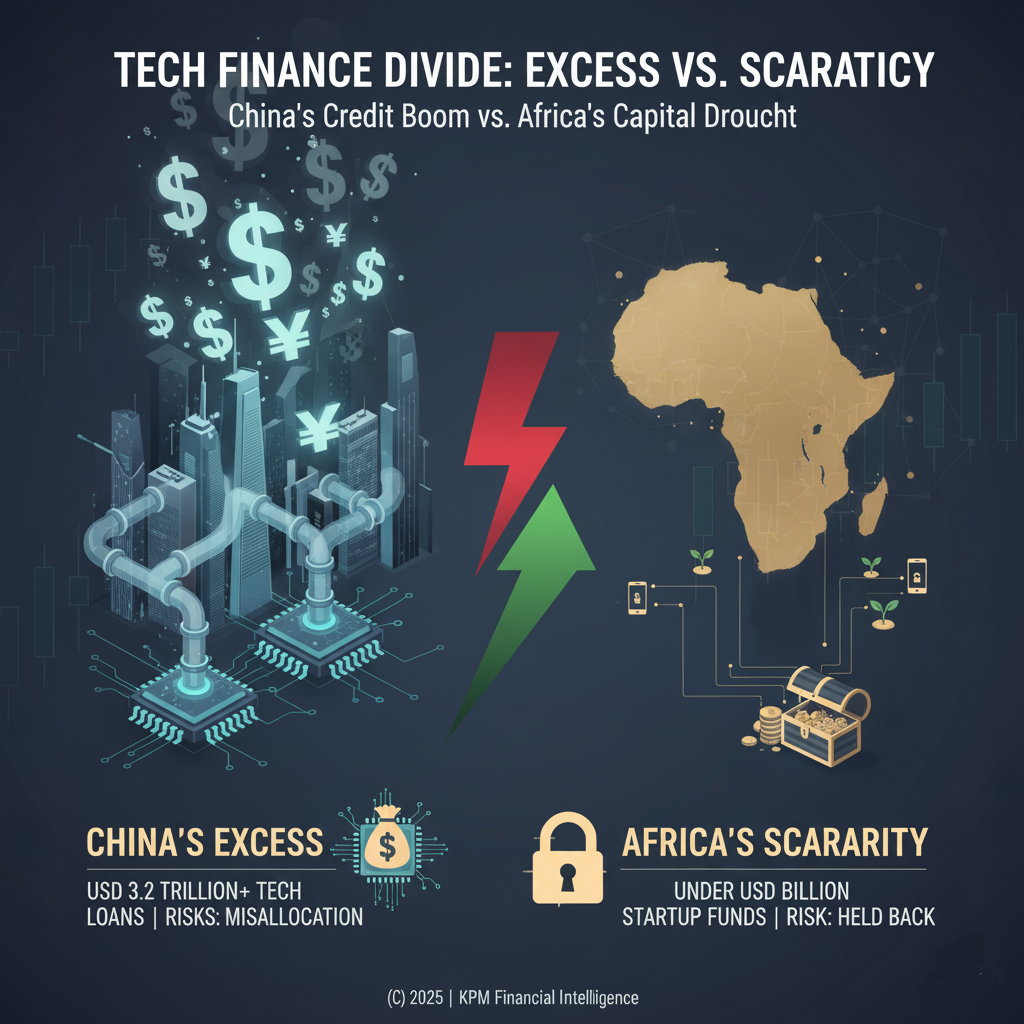

China’s banks deployed over US$3.2 trillion in tech loans by mid-2025, while Africa’s startups raised under US$3 billion in 2023. This vast credit gap shows one system risking misallocation through excess and another held back by scarcity, with major implications for global investors.

China’s banks pumped more than US$3.2 trillion into technology firms by mid-2025. Sub-Saharan Africa’s entire tech ecosystem, by comparison, raised less than US$3 billion in venture capital in 2023. This gulf is not a quirk of statistics but a reflection of two financial systems moving in opposite directions. One is mobilizing credit at unprecedented scale to industrialize its future, while the other is struggling to fund even the most promising innovators. For global investors, the contrast captures both a looming risk in Asia and a vast untapped opportunity in Africa.

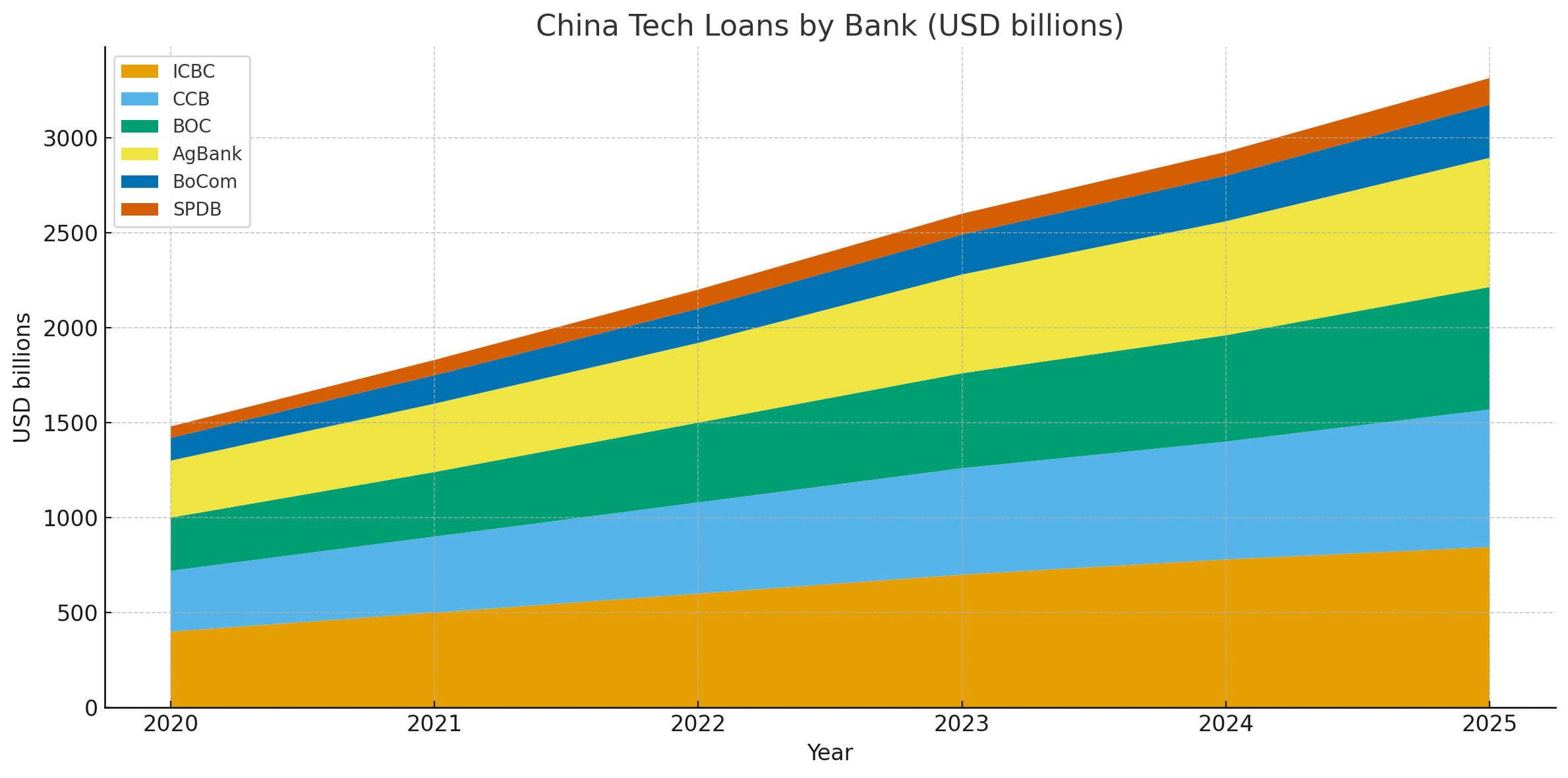

By June 2025, China’s six state-owned banks had amassed nearly ¥23 trillion (≈US$3.23 trillion) in technology-focused loans. Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (HK: 1398, SHA: 601398) alone exceeded ¥6 trillion (≈US$845 billion), more than twice South Africa’s GDP (≈US$405 billion) and nearly forty times Kenya’s GDP (≈US$95 billion). China Construction Bank (HK: 0939, SHA: 601939) lifted its tech loan balance to ¥5.15 trillion (≈US$724 billion), nearly three times Nigeria’s GDP (≈US$252 billion). Bank of China (HK: 3988, SHA: 601988) reported ¥4.59 trillion (≈US$645 billion), a figure surpassing the entire private-sector credit stock of Sub-Saharan Africa, which remains near US$600 billion. Agricultural Bank of China (HK: 1288, SHA: 601288) lifted its tech exposure to ¥4.7 trillion, while Bank of Communications (HK: 3328, SHA: 601328) added 87 dedicated tech sub-branches and rolled out services for more than 80,000 technology firms. Joint-stock lenders such as Industrial Bank Co. (SHA: 601166) and Shanghai Pudong Development Bank (SHA: 600000) each surpassed ¥1 trillion in tech lending.

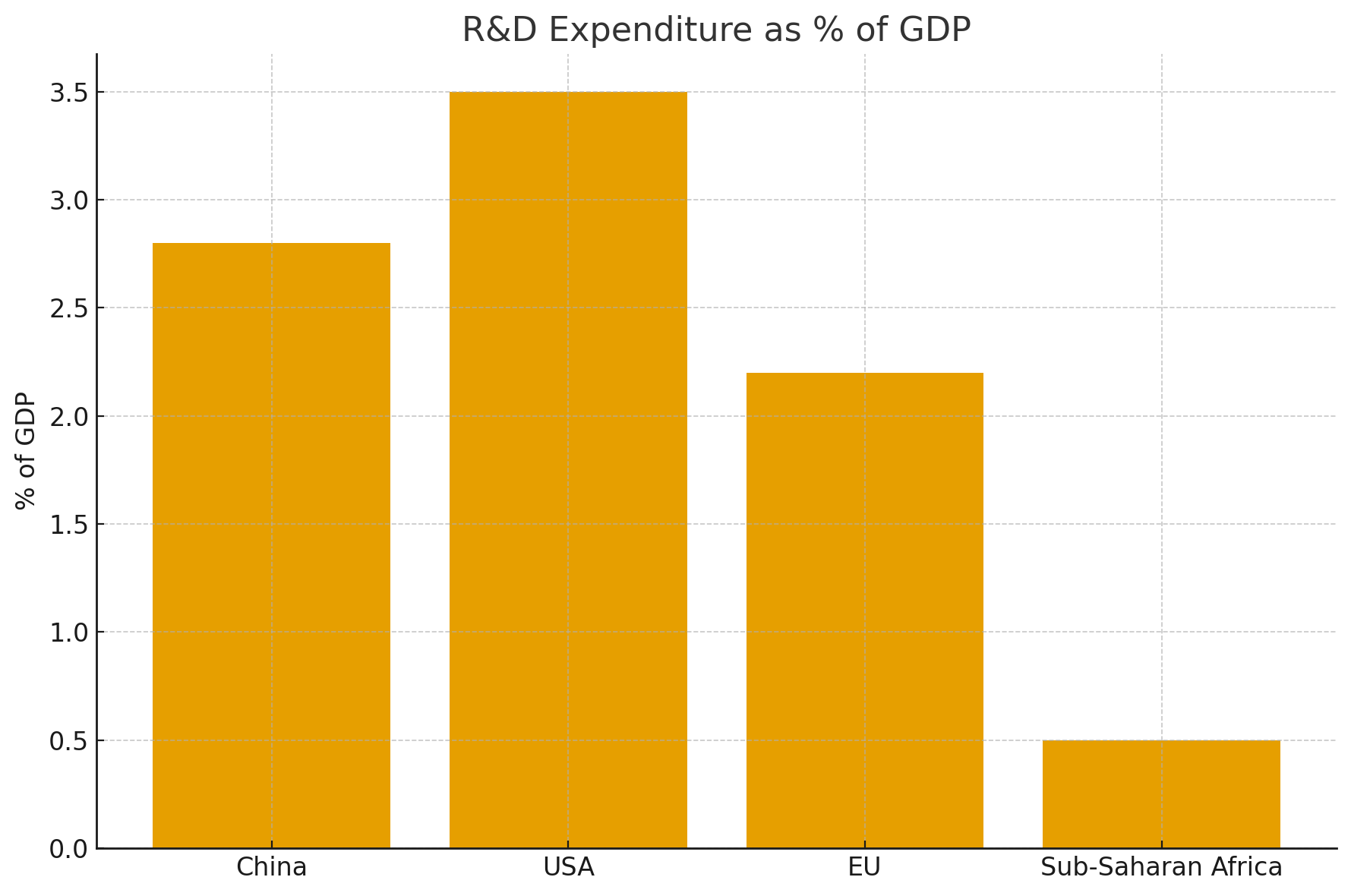

This surge is not accidental. Chinese banks are executing state industrial policy, channelling credit into strategic sectors under Made in China 2025 and the 14th Five-Year Plan. The country aims to raise R&D intensity to 2.8 percent of GDP by 2025, compared with Sub-Saharan Africa’s 0.5 percent average. Lending is designed to close the loop: not just loans, but equity linkages, supply-chain financing, and innovation clusters where banks act as full partners. Credit has become infrastructure, embedding finance into the industrial fabric of a nation seeking technological self-reliance.

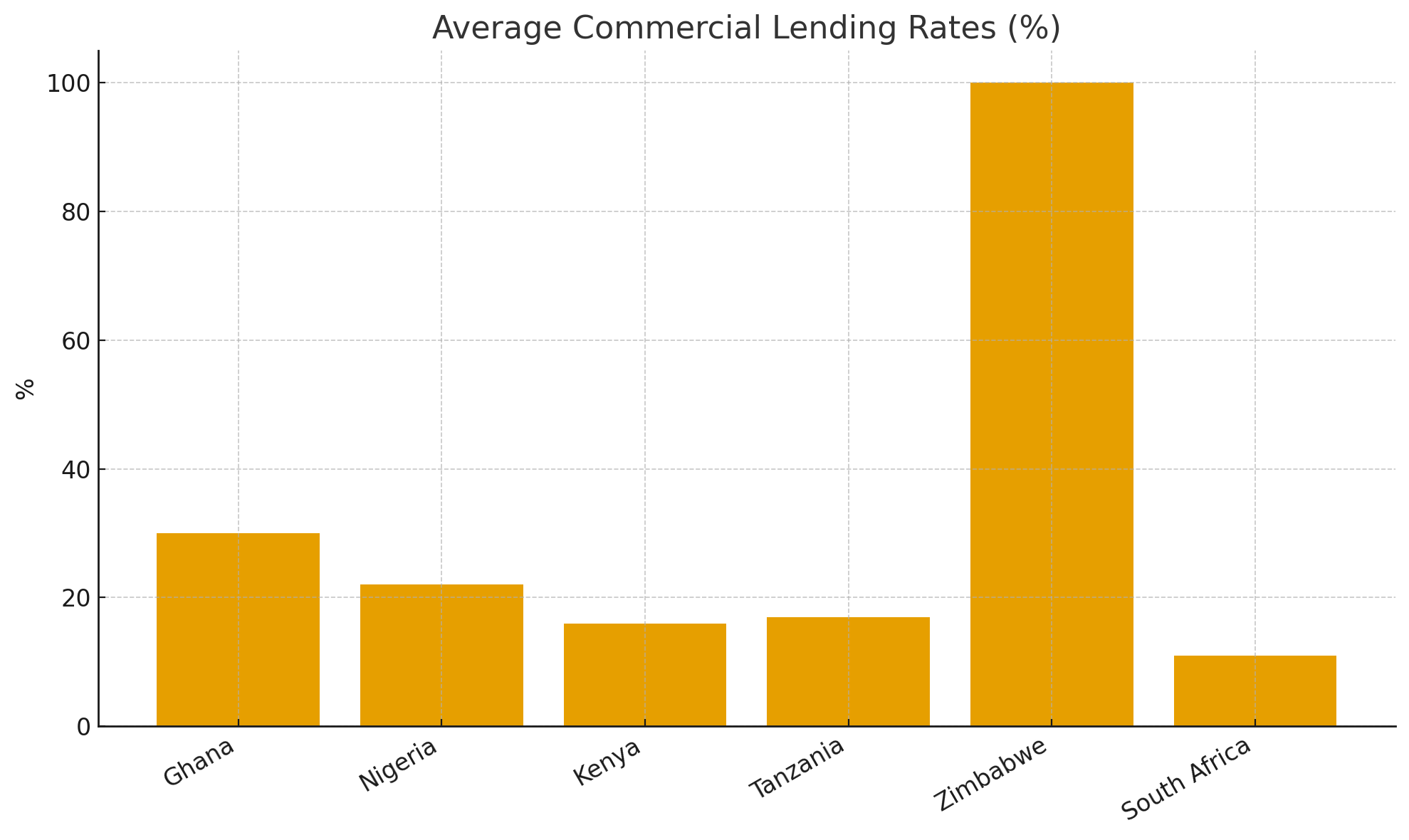

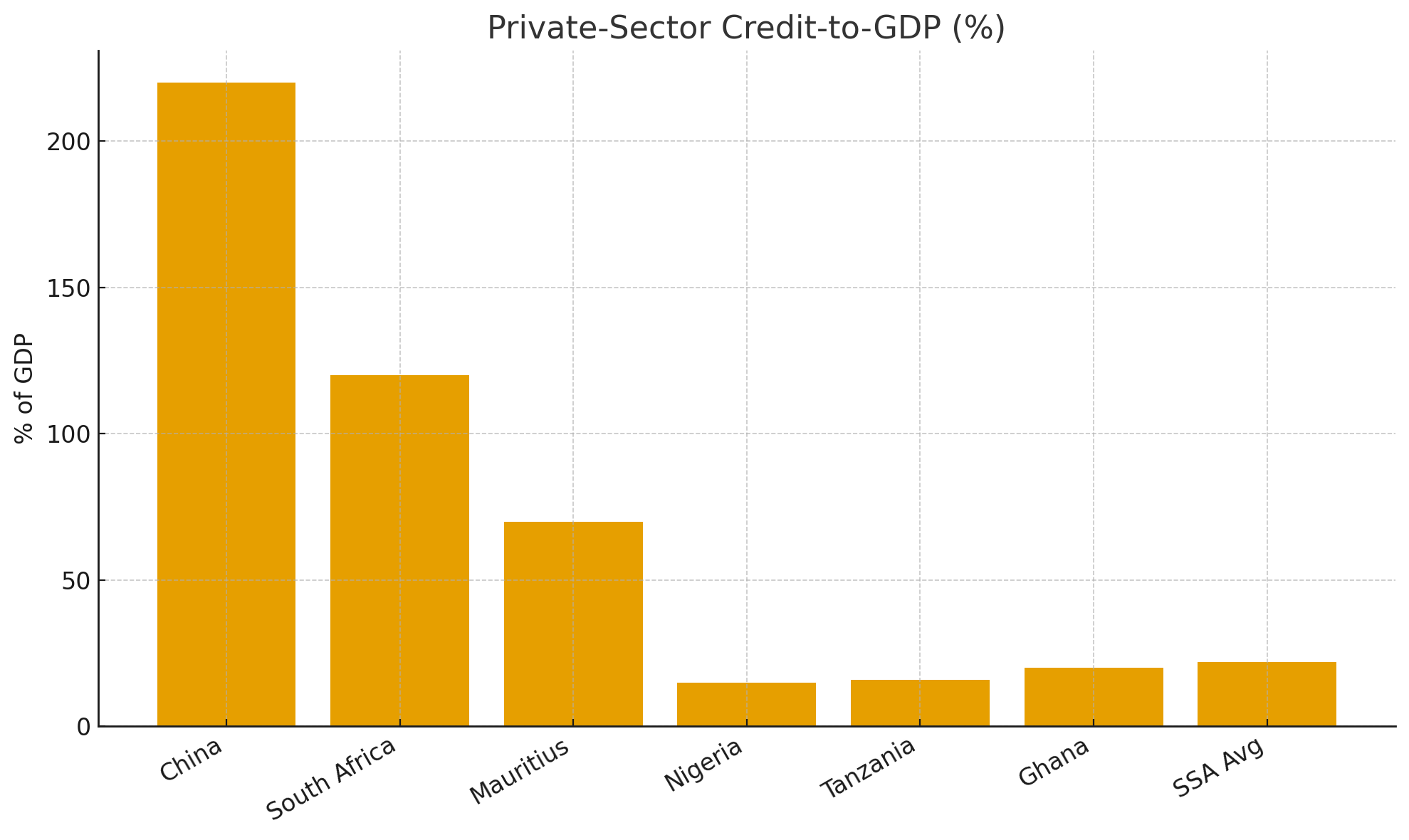

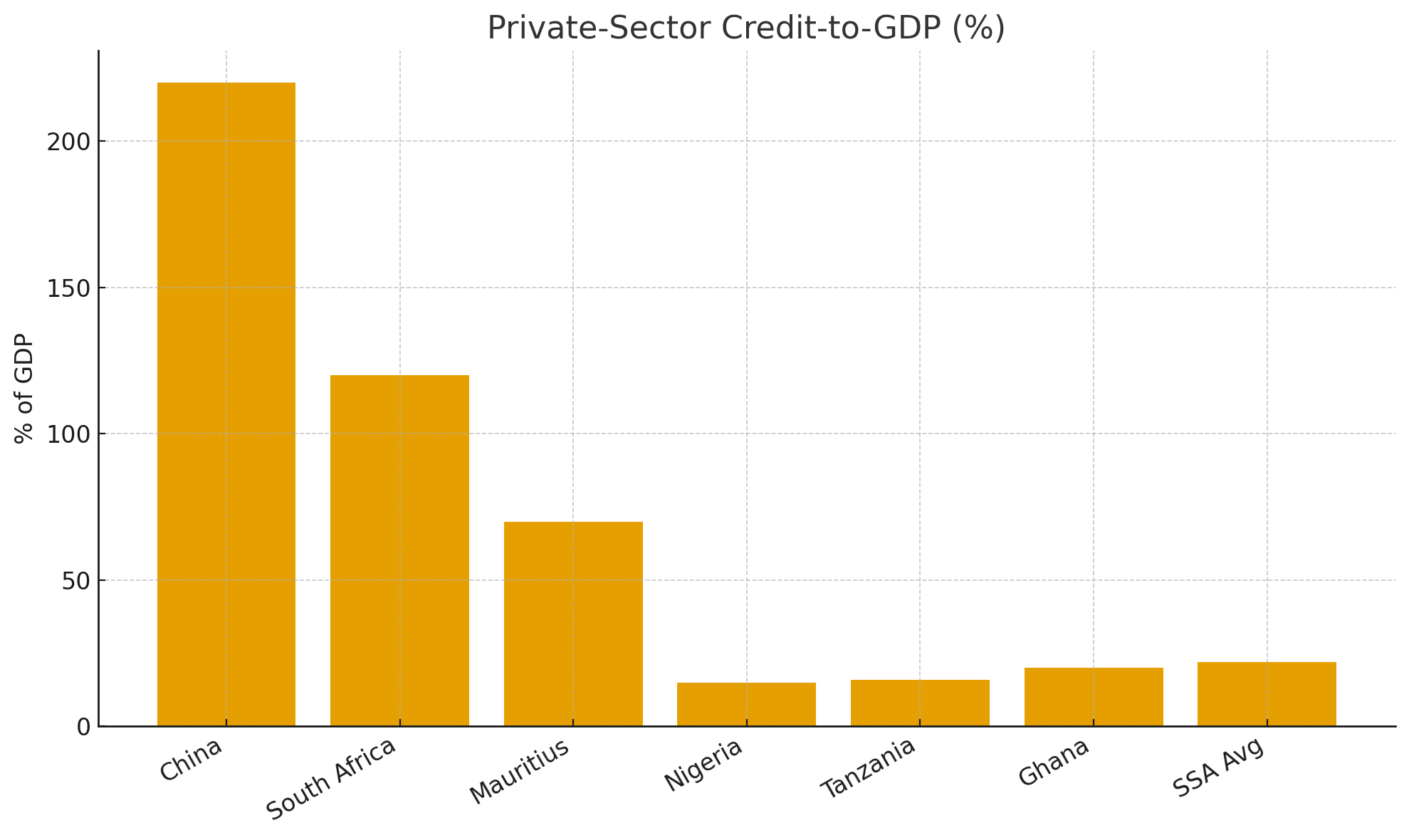

Africa, by contrast, remains constrained by shallow markets and high borrowing costs. Private-sector credit-to-GDP ratios average 22 percent, compared with China’s ~220 percent. Mauritius approaches 70 percent, South Africa hovers near 120 percent, but Nigeria remains at 15 percent, Tanzania at 16 percent, and Ghana struggles to stay above 20 percent. Lending rates often range from 15 to 25 percent. In Ghana, commercial rates exceed 30 percent; in Zimbabwe, they climb above 100 percent, effectively excluding SMEs and tech startups from bank finance. Kenya’s private-sector credit growth contracted by 2.9 percent year-on-year in late 2024 as sovereign refinancing crowded out private borrowers. In Nigeria, listed banks such as Guaranty Trust Holding (NGX: GTCO) and Zenith Bank (NGX: ZENITHBANK) allocate most lending to oil-linked trade and commodities, leaving innovation starved of domestic credit. Ghana’s central bank policy rate sits at 29 percent, cascading into prohibitive borrowing costs for firms. Even in South Africa, where Standard Bank (JSE: SBK), FirstRand (JSE: FSR), and Absa (JSE: ABG) anchor a deeper financial system, lending still favors miners and property developers over tech firms.

The venture capital story underscores the gap. In 2022, African startups raised US$4.6–5.4 billion, but inflows fell nearly 50 percent in 2023 to between US$2.9 and 3.5 billion. More than 75 percent of this funding came from foreign investors, leaving ecosystems exposed to global liquidity cycles. By contrast, China’s domestic banks added more than ten times Africa’s annual VC inflows in just six months of lending. The result is two divergent innovation trajectories: China can overwhelm markets with patient credit, while Africa remains vulnerable to capital droughts when global risk appetite fades.

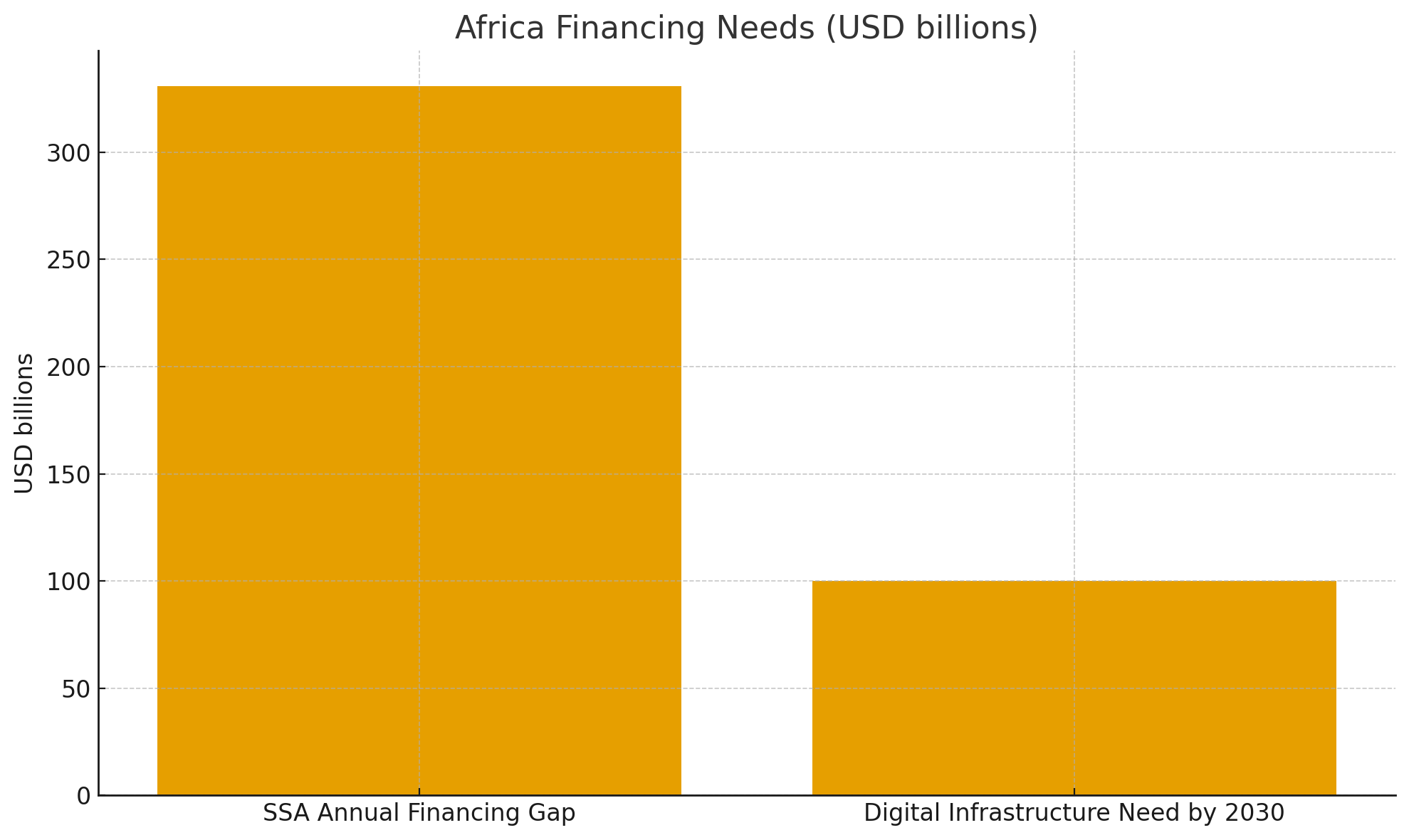

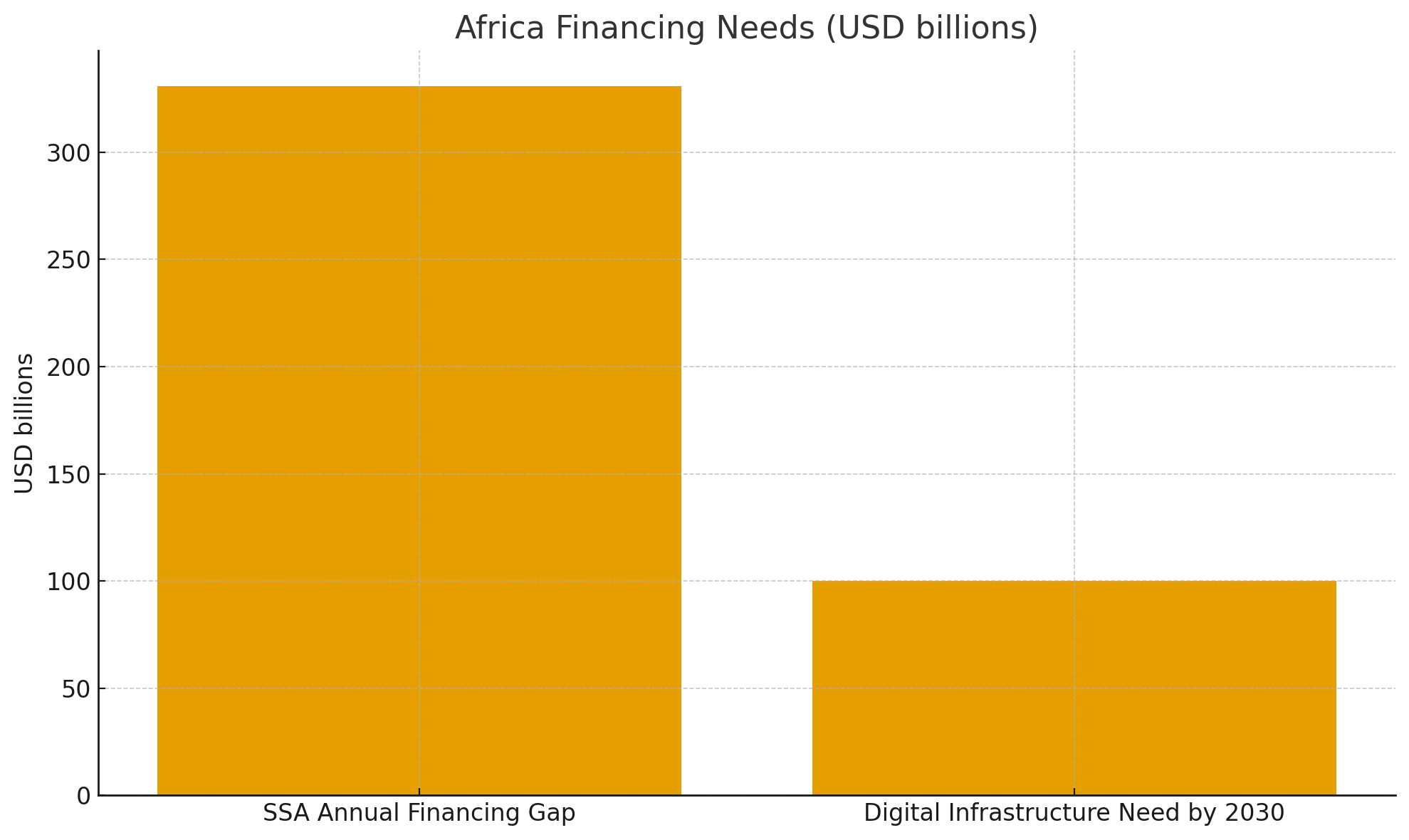

The risks for both regions are mirror images. China risks misallocation. Official non-performing loan ratios remain under 2 percent, but stress scenarios suggest innovation-heavy portfolios could rise to 5–7 percent, especially in sectors like semiconductors and green tech where policy mandates fuel rapid lending. Africa risks stagnation. The African Development Bank estimates an annual financing gap of US$331 billion, with digital infrastructure alone requiring US$100 billion by 2030. Without systemic credit support, even the most dynamic startups will remain undercapitalized, constraining productivity and long-term growth.

The lessons are clear. For Africa, the Chinese example is not a model to replicate in scale but in alignment. Development banks, sovereign funds, and pension pools can be mandated to support innovation finance, while blended instruments—credit guarantees, local-currency risk-sharing, and cash-flow-based lending—can help unlock private credit. For China, the lesson is discipline: lending at this pace risks creating bubbles, so monitoring loan quality, NPLs, and exposure concentration will be critical.

For global investors, the comparison translates into opportunity and risk. In China, prudence dictates hedging against potential credit bubbles and pricing in systemic exposure through listed banks and sovereign bonds (CNY, CNH). In Africa, scarcity itself creates an arbitrage play. Even modest allocations—US$100–200 million through blended finance and currency-hedged structures—can shift market dynamics. In Nigeria, where private credit stock is only about US$90 billion, a single institutional allocation can move the needle. In Kenya, where lending rates exceed 15 percent, blended vehicles backed by DFIs can reduce costs and expand access. Investors already have proxies to capture exposure, from South Africa’s JSE Banks Index (J835.JO) to pan-African funds such as VanEck Africa ETF (NYSE: AFK).

Finance is the decisive infrastructure of the innovation economy. China demonstrates the power, and the peril, of oversupplying credit in pursuit of technological leadership. Africa illustrates the costs of under-financing, where innovators are constrained not by ideas but by access to capital. For global institutions, the strategic choice is clear. Hedge against China’s excess through careful positioning in listed bank equities and sovereign spreads, but seize Africa’s scarcity through patient allocations into banks, fintechs, and blended finance structures. Trillions of renminbi are already deployed in China. In Africa, with credit-to-GDP ratios in the low twenties and borrowing rates still punitive, the space for growth is immense. The question for global capital is whether it will keep chasing saturated markets, or recognize the asymmetric opportunities in under-financed ones.